“Diversity Is A Two-Way Street”: Brand Founders On Changes That Need To Be Made To Support Black Beauty Entrepreneurs

Last week, White House economic advisor Larry Kudlow, a former Wall Street-er and television talking head, denied there’s systemic racism embedded in the fabric of the United States. But its effects are felt throughout the economy, and limit the opportunities available to Black Americans and their chances to succeed at the levels of their white counterparts.

“It’s about the racial wealth gap. I think that is the big elephant in the room,” remarked David Baboolall, senior engagement manager at McKinsey & Company, and is one of the co-leads of the management consulting firm’s McKinsey Black Network and Black Economic Forum. He explained the racial wealth gap undermines the wellbeing and financial security of Black Americans, and it impedes U.S. economic growth. If the country closed the racial wealth gap every year going forward at a rate as fast as the gap narrowed annually between 1989-2016, it would be worth up to an estimated $1.5 trillion by 2028. “What we know about economic mobility is that it’s not evenly distributed across the U.S,” said Baboolall, sharing that only 25% of Black children born into poverty enter the middle or upper classes.

He joined a Beauty Independent In Conversation webinar on Friday moderated by Kilee Hughes, founder of public relations firm Six One, with participants Dorian Morris, founder of Undefined Beauty, Lauren Napier, founder of Lauren Napier Beauty, and Rahama Wright, founder of SheaYeleen, that delved into how the beauty industry can ensure the current spotlight on Black-owned businesses isn’t a passing trend.

Morris, who held executive positions at Cover Girl, Sundial Brands and Kendo Brands prior to launching Undefined Beauty, pointed out retailers haven’t regarded Black-owned brands and white-owned brands equally, and she noted there’s a distinction between Black-owned and Black-led brands. Many of the brands major beauty retailers tout in their inclusivity pushes aren’t entirely Black-owned. For example, Rihanna is a minority owner of Fenty Beauty, the makeup brand the pop star developed with LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton’s incubator Kendo. Black entrepreneurs Nyema Tubman and Richelieu Dennis founded Shea Moisture, but Unilever acquired it three years ago.

“It doesn’t make them less than, but it’s a different paradigm,” said Morris of the Black-led brands. “Yes, they do amazing things for the community, but it is a very different dynamic. There is a focus that should be placed on the independent businesses. We are the ones that need the support and resources the most.”

The beauty industry has been guided by beauty standards that exalt whiteness. They drive decisions about investment and retail real estate. Napier shared experiences of decision makers being surprised by her race when she’s walked into meetings. “I had buyers say, ‘Oh, this doesn’t look like a Black-owned brand,’” she recounted. “What does a Black-owned owned brand look like?” Napier’s brand encountered initial pushback from editors and buyers wondering if white people would buy its cleansing wipes. Net-a-Porter now carries Lauren Napier Beauty.

“Diversity is a two-way street,” said Napier. “There’s an idea of what a Black brand is supposed to be and what it’s supposed to represent, and that it is pigeonholed to just a certain community.”

Baboolall outlined five stages of entrepreneurship. Ideation and startup are the first two. One-fifth of Black Americans are starting and running new businesses, more than any other racial group, and Black women in particular own businesses at a much higher rate than other minority groups. Black business owners face major roadblocks in later phases of entrepreneurship, including sustaining and scaling, a stage often requiring an influx of capital. Only 4% of Black Americans run established businesses that have existed longer than three and a half years. The average Black-employer firm has approximately $860,000 in annual revenues. In comparison, white-employer firms have approximately.$2.4 million in annual revenues during the scaling phase.

It’s crucial to assist Black-owned brands in going from startup to scaling to have the possibility of lucrative exits. Napier helped establish Consider Something Better, an initiative aiming to raise $5 million to support Black women entrepreneurs with funding. In 2016, Project Diane discovered Black women founders were part of a mere .2% of venture capital deals from 2012 to 2014. Even before venture capitalists are involved, Napier said friends and family funding rounds pose greater challenges to Black founders than white founders. She explained, “We don’t have the generational wealth that can support a friends and family round for capital.”

According to Nielsen, the spending power of Black Americans is valued at $1.2 trillion, and Napier believes big corporations have a responsibility to give back to the communities building their businesses. She said, “That’s the only way to have economic prosperity and equity, and to move the entire economy forward.”

“There’s an idea of what a Black brand is supposed to be and what it’s supposed to represent, and that it is pigeonholed to just a certain community.”

Wright’s brand SheaYeleen is dedicated to empowering women in West Africa producing shea butter. It entered Whole Foods stores in the grocer’s North Atlantic region thanks to a program dedicated to the next generation of conscious capitalists. SheaYeleen’s early customers were white women living in small towns interested in the brand’s ethos, but Wright acknowledges she’s had trouble scaling the brand beyond its nascent phase. She mentioned there are several investment funds that put Black in their descriptors, but the travails of being a Black entrepreneur haven’t subsided. “We don’t see the impact of what is happening with those funds,” she said, calling for increased data on and reporting about Black-owned businesses to amass evidence for stronger cases for investing in them.

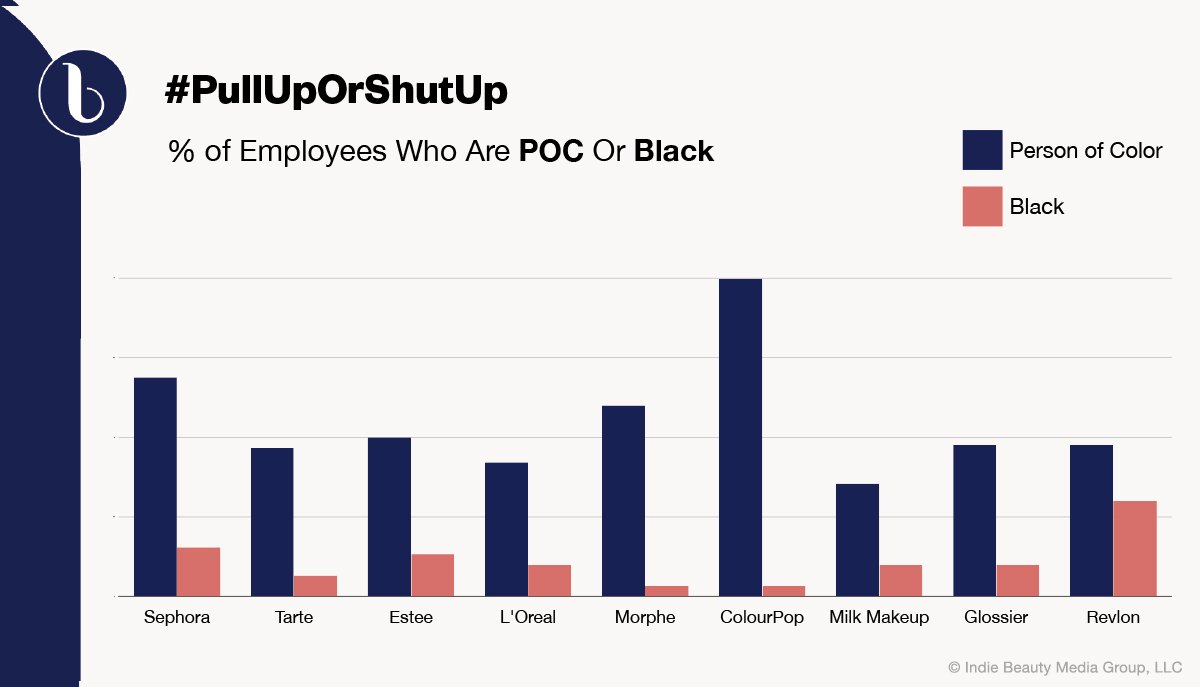

New efforts such as the 15 Percent Pledge asking retailers to commit 15% of shelf space to Black-owned brands are sparking conversations about elevating Black-owned brands’ access to customers. The hope is that they will hold companies accountable for their actions over the long term. Morris said, “Ultimately, consumers vote with their dollar. There are a lot of companies making money off of the Black dollar who don’t have the staffing to represent that.”

Napier emphasized, “This should not be where it stops.” She continued, “If you have a hundred businesses, you don’t want just 15 to be Black woman-owned and allocated, there’s your 15, don’t talk to me anymore. We want to make sure that that in fact grows so additional businesses [are incorporated], and 15% are paving the way, but it creates opportunity for more businesses to grow.”

Wright stressed conversations around representation and opportunity should extend beyond U.S. borders. “At the beginning of these supply chains are a lot of Black and brown people who are living in poverty, yet are supplying natural ingredients, supplying raw ingredients to multibillion-dollar companies. There are no cocoa plantations in the U.S. We’re not creating shea butter,” she said. “My question is, ‘How is it impacting a person in a small village in X country?’ CPG companies, whether larger, small, whether indie or not, we need to start being inclusive from the beginning of the supply chain. And I think that it behooves us to look at the entire ecosystem, not just what’s happening to Black and brown people here in the U.S.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.