How Indigenous-Owned Brand Satya Is Helping The Kamloops Community After The Discovery Of 215 Buried Schoolchildren

“When the news came about, I wasn’t shocked,” says Patrice Mousseau, the Vancouver-based Ojibway founder of Satya Organic Skin Care. “Initially, I was like, yes, of course they found that—and they’re going to find more. I’ve seen so many traumas inflicted upon First Nations people. Of course, there’s this.”

The news Mousseau refers to is the June 1 discovery of the remains of 215 schoolchildren on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. Operating throughout Canada from the 1870s until the 1990s, church-run residential schools worked to forcibly assimilate more than 150,000 Indigenous children into white settlers’ culture. Widespread reports of physical abuse, sexual assault, food deprivation and other appalling cruelties at the residential schools have surfaced. In 2008, Stephen Harper, then the Canadian Prime Minister, publicly apologized to residential school students.

Mousseau couldn’t bring herself to speak about the Kamloops Indian Residential School horror at first, but, after a few days of reflection, she emerged with a plan to assist people in the city where it took place. Here’s the Satya founder’s account of becoming an unexpected beauty entrepreneur, and using her brand as a vehicle for social change in Canada and beyond:

I am Anishinaabe, that’s Obijway, and my family comes out of Fort William First Nation. I always knew who I was, and I always felt very connected to my identity, but my grandmother was taken away from her family and put in a residential school. When she married my grandfather very young, she became his property. She was no longer considered to be an Indigenous person by the Canadian government.

The fact that my grandmother had lost her status because of becoming married to my grandfather, who was French, meant that my parents didn’t have to go away to residential school like she did. In a way, she was protecting her kids by not being deeply invested in her community. So, in a lot of ways, I feel like I’m reclaiming a lot for my family, for my grandmother. For me, [being Indigenous] was always an incredible thing to be, and it became sort of the driving force throughout my whole career.

I was a journalist for many years. I had a show on our big talk station in Toronto called CFRB. I was the program director at Aboriginal Voices Radio Network. I was the national news anchor for APTN. Honestly, I thought that’s what I was going to be doing for the rest of my life. I saw the media as a way to shape culture and a way to make the world a better place. I wanted to change the world.

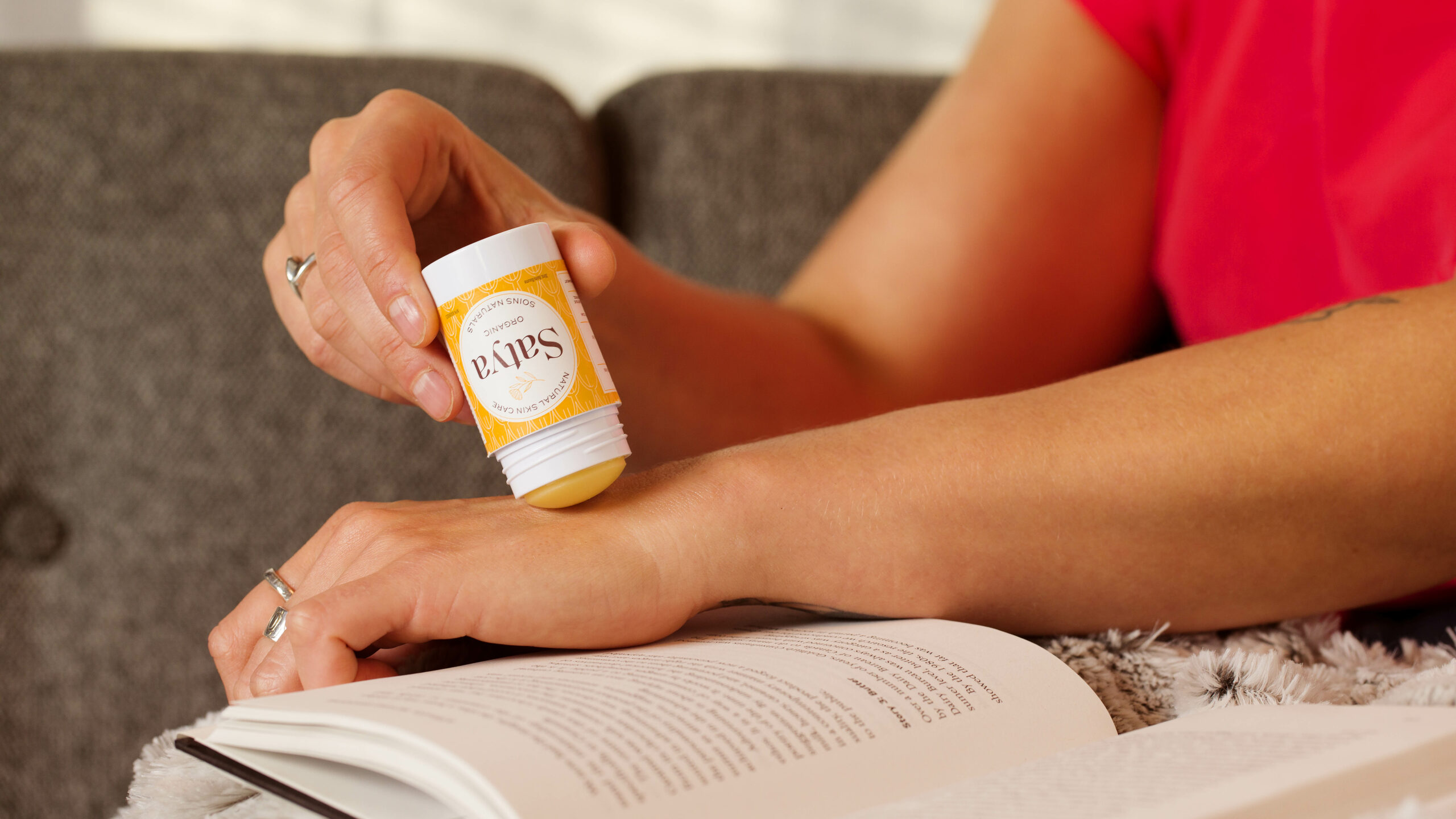

Then, I had my daughter Esme in late 2011, and your whole perspective changes. I’d lost the glow for what I was doing. When I started [making skin salves] for her, it had nothing to do with business. There was a desperate need for me to find some way to help my child with her eczema, and the resources that I had were my research skills. I’d seen news stories about the detriments of using steroids. I had interviewed people who had authored books on the dirty dozen and all these different things that you shouldn’t have in your products.

I went looking for something over-the-counter for her because I refused steroids, and what I found was all full of garbage. I was like, “You know what? I’m going to look at the existing medical research that’s out there, and I’m going to look at traditional medicine and just try to merge everything together.” So, I did. I merged it in my little kitchen crockpot that I bought used on Facebook for 15 bucks. After a little bit of experimentation, I created something that cleared Esme’s eczema up in two days.

Then, I’m like, “OK, well, I have this whole bloody crock pot. What am I going to do with this?” I went back on Facebook, and I said, “Does anybody else need any?” At this point, I didn’t realize the extent of the problem. Twenty percent of the world’s population under the age of 8 suffers from eczema. That’s huge! And adults aren’t that far behind. I had people driving from towns over to come and get some of this because everybody was saying it was working so well. I ended up making like three more crock pots right away. I wasn’t advertising or anything. I was charging just enough to cover my ingredients, really, not even my labor.

My perspective of business has always been very negative. It’s always been “Wolf of Wall Street,” guys in suits, spreadsheets, math—just basically screwing people over for money. It’s always been about profit, and that was never my driver. But, about a year and a half later, I went to this women’s entrepreneurship conference. I saw these incredible women who had businesses that were not only successful, but also led with integrity. These women were doing business in such a way that it was actually a vehicle for social change. It was inspiring. I thought, you know, I’m going to try.

When I created my company in 2014, I named it Satya. I wanted it to mean truth. That’s what Satya means [in Sanskrit]. I got everything set up, and I did a farmers’ market out here in Vancouver. I sold $110 worth of product, and it was amazing! I couldn’t believe that someone that didn’t know me was buying something that I created.

“When you’re an Indigenous business owner, the thought of community is inherent. One of the first things you think about is, ‘How do I give back to my community while I’m doing this?'”

After I went to a farmers’ market, then I went to a local kids’ store, and I was like, “Would you consider carrying my product?” The owner said, “No! I already have 100 different products. I don’t need another one.” I said, “Do you have any skin problems?” And she’s like, “Yeah, I’ve got this rash on my ring finger. It’s itchy, and it drives me crazy.” I said, “Here, take a travel size, and I’ll call you back in three days. Let me know how it goes.” She calls the back the next morning, and she says, “My rash is gone. I’ll carry your product.”

After that, through word of mouth, we ended up in 70 stores in the lower mainland. And, then, Whole Foods calls in 2016, and they’re like, “We want to start carrying your product.” I was like, “That’s awesome, but I’m still making this in my crock pot. You’ve got to let me ramp up.” I ramped up with production, got a full lab going and got somebody to help me. I got a distributor as well. We went from 70 stores to 400 stores in two months. Now, we’re in over 900 stores in Canada.

We’ve also been planning to go into the U.S. We were getting our fulfillment center and our inventory system set up. I don’t know how this happened, but Kroger.com called us this year. So, now we’re on Kroger.com. They’re just the first U.S. retailer. We’re looking at others. We want to find other great values-based e-commerce platforms that want to have an Indigenous brand that’s very clean and effective, and just does good in the world.

When you’re an Indigenous business owner, the thought of community is inherent. One of the first things you think about is, “How do I give back to my community while I’m doing this?”

I’ve been looking at all these different stick options [to hold the balm], and none of them were right. Bioplastics turn to microplastics. Paper falls apart. I thought, “Well, what if we got a really high-quality plastic and made it refillable?” Now, all of our sticks you can refill with our refill pouches, which are made from non-GMO corn and wood fiber. They’re actually compostable. In addition to that, because we are producing some plastic, we offset all of it with a company called the Plastic Bank.

Whenever someone buys one of our sticks, we’re actually paying someone in a developing country to go to their local waterways and pull plastic out. They then take it to the depot for recycling, and they exchange it for credits for medical care, educational tuition or household items. It’s addressing not only ocean plastic, but global poverty as well. That’s one of many things that we’re doing.

Right now, we’re also promoting support for the Kamloops Aboriginal Friendship Society. They’re in desperate need of a new building, and they need about 2 million dollars. We’ve been trying to get people to donate to that because that’s a real, tangible thing that can make a difference to that community.

A few days [after the news about the buried children came out], that’s when I decided that all our efforts were going to go to supporting the friendship center there because friendship centers are like the heart of a community. We wanted to be able to show that we weren’t just sending “thoughts and prayers.”

This is our everyday reality. I had to have a conversation with my daughter explaining this to her. And she asked me, “Do I have to go? Do I have to go to residential school?” This is what we live with. So, I’m glad I guess that this [news] is reaching more people. We just do what we can. I want to give people the tools to help themselves.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.