What Does America’s Shrinking Middle Class Mean For The Beauty Industry?

In journalist Fareed Zakaria’s book, “Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World,” The Washington Post columnist and host of CNN show “GPS” muses over the ways COVID-19 has forever changed the world, from people’s relationship to work and technology to the imperative for trustworthy governments and science-led policies. Out of all the issues he finds pressing, he identifies the rapid rise of economic inequality as the direst.

“For the last three recessions, the top 25% and the bottom 25% lose jobs at about the same rate. In this recession, the top 25% have actually stayed stable,” he told Terry Gross, host of the NPR program Fresh Air, in October last year. “This massive acceleration and exacerbation of inequality is, to me, the most deeply worrying thing about what this pandemic has done.” It’s a worry that has been echoed widely by thinkers across the media, academia and political institutions, including at the Financial Times, a publication that’s decried American middle class stagnation, and inside the Biden administration, which recently shepherded the American Rescue Plan into law to address many of the inequities laid bare by the pandemic.

The squeezing of America’s middle isn’t a new development, points out Marshall Reinsdorf, an economist who’s served as chief of the United States Department of Commerce’s National Economic Research Group for over a decade. “You can start to see inequality tick up in the ‘70s,” he says, adding, “The bottom half has always suffered more when recessions come along, but I will say that, historically, the job market has come back faster [in the past].”

In 2018, The Pew Research Center defined the American middle class as households of three earning $48,500 to $145,500 annually. About half of U.S. households classified as middle class that year. Nearly 30% were lower-income households, and 19% were upper-income households. The middle class is far from what it once was. In 1971, 61% of American households classified as middle-income. By 2019, the proportion of middle-income household earners had dropped to 51%.

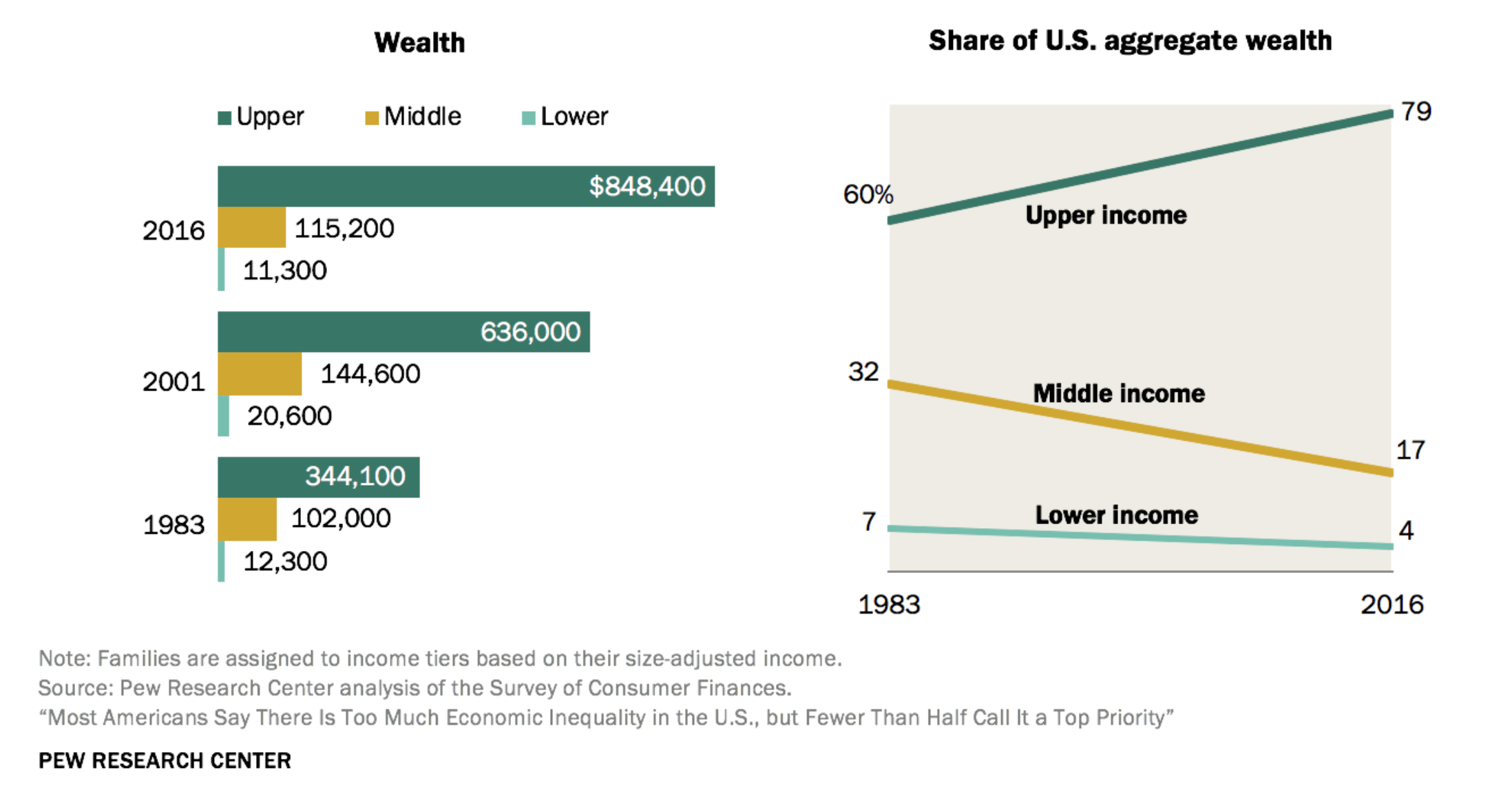

As Americans face the pandemic-stoked recession, Reinsdorf says, “Polarization has gotten worse…The people at the low end of the job market have suffered the most, those in the middle have suffered second most, and the people at the top haven’t really suffered much at all.” The yawning divides become clearer with an examination of wealth distribution in the U.S. “A lot of people like to talk about income, but you can get a bigger picture when you look at wealth,” says Reinsdorf. “[The entire] bottom half has almost nothing [compared to the top 1%].”

The bifurcated economy obviously has profound societal, moral and legislative implications, but it also has effects that reverberate throughout the consumer goods sector, including the beauty business. What will it take for beauty brands to survive and thrive in a country with a cavernous gap between haves and have nots? Certainly, product pricing is a factor. However, it’s far from the only factor. Competing in an America filled with consumers that live divergent realities requires a high level of deftness to navigate perceptions of value, household constraints and the complexity of a labor force linked with the vagaries of the service industry. The beauty business that emerges to deal with the hollowing of the middle class is likely to topple the barriers that characterized it in prior epochs.

The pandemic has revealed the vulnerability of upscale beauty—and potential opportunities from traditional boundaries in beauty retail being further eroded. Larissa Jensen, vice president and industry advisor at The NPD Group, says, “Prestige brands have lost dollar share over the past year to mid-range brands as well as mass brands.” She reasons the dollar share shift can’t be boiled down to merely economics. “There is the element of the shrinking budgets. Obviously, there’s been a lot of challenges,” says Jensen. “The other [part] is around the brands themselves. A lot of brands expanded distribution into the prestige space and, with that, kind of drove that performance.”

The Ordinary, a skincare brand Sephora is currently touting for its serums priced under $10, is a key example exhibiting that, even in prestige environments, affordability has become prized. Sephora seemingly has built upon the lessons of injecting The Ordinary into its skincare assemblage. It’s gathered a clean makeup assortment hitting a range of price points to ensure that consumers with varying spending capabilities can purchase clean makeup items. Westman Atelier’s foundation stick is $68, Merit’s foundation and concealer stick is $38, and LYS Beauty’s serum foundation is $22. Speaking of accessible beauty at prestige retail, Jensen says, “What you can’t deny is that the consumers responded.”

“Prestige brands have lost dollar share over the past year to mid-range brands as well as mass brands.”

Masstige, a segment blending mass and prestige typically thought to occupy intermediate ground price-wise between top-tier department stores and discount venues, has come to the fore with prestige beauty’s softness. Retail tie-ins are prime masstige movers. There’s Ulta Beauty’s partnership with Target that’s slated to ultimately place Ulta installations at 1,900 Target doors, and Sephora’s collaboration with Kohl’s, an arrangement that could yield 850 Sephora shop-in-shops in Kohl’s units across the country. Masstige beauty retail in the U.S. has been attempted previously at concepts such as Duane Reade’s Look Boutique. Still, it’s relatively novel domestically. Abroad, Jensen suggests there are plenty of models at the likes of City Pharma in France and Shoppers Drug Mart in Canada.

“[We are seeing mass] brands selling in the prestige channel, but we see the reverse as well,” says Jensen. City Pharma sells Caudalie next to Avene, and Shoppers Drug Mart stocks Nars alongside CeraVe. “I’ve been saying forever the consumer does not shop in a particular channel. She shops wherever she is,” says Jensen. “Just like everything else in 2020, it just accelerated what was already happening.”

For beauty shoppers, purchasing luxury and mass products in the same transaction could necessitate some getting used to, but retailers are betting the combination will increase basket sizes. “The pandemic shopping mindset opens doors for masstige brands to engage with a larger array of shoppers than ever before,” says Lauren Goodsitt, senior global beauty analyst at Mintel. “Masstige and prestige brands have the opportunity to engage with consumers during the decision-making process, hence giving them reasons to invest and showing them areas to save.”

How Ulta and Target, and Sephora and Kohl’s design and execute their partnerships will have enormous impacts on the future of masstige in America, but they’re certainly not the only retailers inclined to high-low merchandising. Costco, the warehouse retailer better known for huge bundles of bar soap and shampoo than expensive eye creams, has added prestige beauty brands like Boscia, Anastasia Beverly Hills and Surratt Beauty to its roster. In a Q4 2020 earnings call, Costco CFO Richard Galanti called “health and beauty aids” a top-performing category.

Jensen notes discount retailers like T.J. Maxx and Marshalls have responded to the demand for better selections of cheaper goods by stocking stores with more purpose—beautiful displays, full collections, expanded breadth—instead of abbreviated tables that feel more like cash-wrap impulse buys. As they upgrade their beauty presentations, off-price retailers and dollar-store chains have the capacity to grab portions of beauty spending. The brand developer Maesa has launched Root to End at Dollar General, a clean beauty haircare line that wouldn’t be incompatible with costlier stores. The line is evidence that dollar-store chains recognize economic winds could be in their favor for beauty buying.

For high-end beauty brands, the blurring retail lines pose a challenge. What will luxury beauty customers make of brands that have exposure in mass chains? Goodsitt stressed palpable delineations are important for companies that prefer to keep their distribution channels separate. “Shifting economic conditions have made consumers closely examine their spending,” she says. “As masstige offerings rival the formulations and packaging of prestige products, the two sectors must provide clear differentiation to help consumers decide when to save versus splurge.”

As they cultivate upper classes that have accumulated wealth, doubling down on their connections to them will be prominent tactics at luxury beauty brands. In an interview with Vogue Business, Jane Hertzmark Hudis, executive group president at Estée Lauder Cos. Inc., said the prestige beauty authority is leaning into digital sales and Chinese shoppers. She explained, “The products still have to be sold in a prestige channel, whether that’s in-store or online, and they have to deliver on a high-touch experience that really nurtures the customer.”

Estée Lauder Cos. Inc.’s emphasis on China is a strategy that will be repeated at traditional luxury beauty companies rather than slashing prices. Morgan Stanley Research predicts China’s role in the luxury beauty market will soar. In a 2019 report, it wrote, “China’s share of the global beauty market could increase by 66% over the next five years, representing a sales increase of about $38 billion—and nearly half of global beauty growth.”

“The pandemic shopping mindset opens doors for masstige brands to engage with a larger array of shoppers than ever before.”

The battle for beauty consumers is occurring online as well. “In a post-COVID world, e-commerce has accelerated by about five or six years of growth,” says Caitlin Strandberg, a principal at Lerer Hippeau, a venture capital firm backing Topicals, Parade and Studs. “Consumers like to buy online…At the end of the day, you have to be where your customer is.” Jensen believes e-commerce could be the greatest threat to the luxury market. “We’ve been calling it ‘product democratization’ where it kind of evens the playing field,” she says. “It’s really hard to create the environment of a luxury brand online since luxury is, by nature, experiential. It’s personal touch, right? And online is the complete opposite of that.”

In digital environments, where the in-store education and attention distinguishing luxury brands can’t be replicated, the prowess of direct-to-consumer specialists at shaping seamless experiences may be the real luxury. And the DTC brands can match the luxe formulations of their steep competitors at lower prices if they forgo the overhead of retail distribution. “Luxury brands trying to play online is just as scary as a prestige brand trying to play in this kind of middle environment,” says Jensen. “It’s going to be a very interesting couple of years.”

In stores and online, what gen Z customers value—and will pay for—could transform the entire beauty market, from off-price to posh. Competition could be fierce among retailers and brands vying for gen Z coins in the growing movement toward minimalism in the name of sustainability. For gen Zers, a single eco-friendly, inclusive, clean serum can be more valuable than three that don’t represent their ethics. If their ethics translate into shopping habits in the long term, lower-priced goods may not always win out.

“We don’t yet know how price sensitive gen Z is, but [we do know that] they’re not afraid to spend more for brands that reflect their feelings and values and represent them,” says Strandberg. She adds that, while gen Z consumers don’t have substantial income to wield just yet, “they do heavily influence their parents spending habits.” Strandberg asserts, “Gen Z is one of most social cause-driven groups in the world…They want their dollars to go to something bigger than purchasing a product.”

For those hunting for signs that luxury beauty in the U.S. isn’t dead, Jensen suggests there are definitely categories that deliver them. “If you look at fragrances for example, and what happened in 2020 and what we still see playing out into 2021, is the areas that are growing in fragrance are the expensive areas,” she says, remarking luxury candles are demonstrating strength, too. “And then in skincare, you see almost the reverse. The higher the price in skincare, the more challenged the category is.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Compared to previous recessions over the past 50 years, which saw job and wealth loss across socio-economic groups, the pandemic-sparked recession has been felt most drastically by low-wage workers.

- The implications of the bifurcated economy for the beauty industry are profound. To thrive in it, brands must be respond to how and where consumers are shopping in the post-pandemic landscape, justify the prices of their products across categories, and address values that drive gen Z consumer purchases.

- According to Caitlin Strandberg, a principal at venture capital firm Lerer Hippeau, “We don't yet know how price sensitive gen Z is, but [we do know that] they're not afraid to spend more for brands that reflect their feelings and values and represent them.”

- Masstige retail is likely to grow. The partnerships between Sephora and Kohl’s, and Target and Ulta provide evidence that retailers are cognizant of the barriers that traditionally divided beauty retail increasingly coming down.

- The yawning gap between haves and have nots doesn’t mean cheaper products will fly off shelves faster. Lauren Goodsitt, senior global beauty analyst at Mintel, notes that there is an opportunity for brands and store associates to increase overall sales by teaching customers when to splurge and when to save.

- Retailers like Dollar General, T.J. Maxx and Marshalls are primed to compete for budget-strapped mass and discount beauty shoppers, while Costco could be poised to increase its inroads into prestige beauty. In a Q4 2020 earnings call, Costco CFO Richard Galanti called “health and beauty aids” a top-performing category.

- Instead of competing for masstige dollars, traditional beauty conglomerates are likely to double down on their luxury customer base in Asia. “China's share of the global beauty market could increase by 66% over the next five years, representing a sales increase of about $38 billion—and nearly half of global beauty growth,” predicts Morgan Stanley Research.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.