Beauty Unit Economics: Why Contribution Margins Can Make Or Break Your Brand

Looking across our beauty industry investments, we have noticed something striking: Many founders who excel at product development and brand building often struggle with the nuts and bolts of unit economics. Yet these “boring” numbers ultimately determine whether your beautiful brand thrives or barely survives.

We know unit economics can feel dense. We promise this deep dive will break down the nuances of unit economics so you can walk away with clarity on what actually drives profitability in beauty. So let’s get practical about the numbers that matter.

Beyond Basic Gross Margin

What You Need to Track

When most founders think about product profitability, they focus on gross margin—the difference between your product’s selling price and its Cost of Goods Sold or COGS. You’ll also hear VCs obsessing about gross margin percentage benchmarks like “minimum” gross margins of 80% in prestige and 60-65% in mass. That’s just scratching the surface, and a focus on percentages alone can lead you astray.

What you really need to understand is your product contribution margin. Product contribution margin is the amount of revenue from selling a single product that remains after subtracting the variable costs directly associated with producing and selling that product. It represents how much each unit sold contributes to covering the company’s fixed costs and, once those are covered, to profit. It varies significantly by channel. As brands scale, so must their understanding of this critical concept.

Product contribution margin is Contribution Margin per Unit = Selling Price per Unit – Variable Cost per Unit.

This metric allows businesses to assess the profitability of individual products and make decisions about pricing, product portfolio and whether and how to promote, continue or discontinue a product. It is also a critical calculation to assess channel profitability. A higher contribution margin indicates that more revenue is available to cover fixed costs and generate profit.

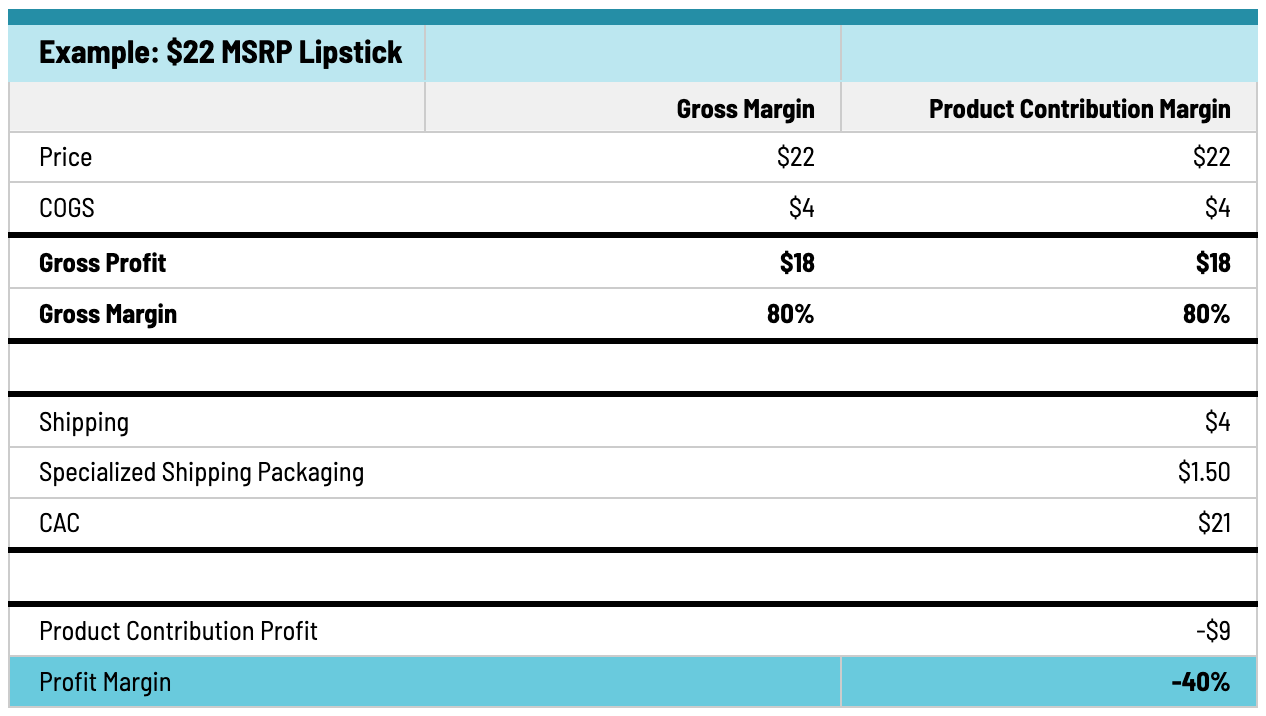

To take a concrete example: A $22 liquid lipstick with 80% gross margin sounds fantastic on paper. But when you add DTC-specific costs like individual shipping at $4, specialized shipping packaging at $2 and customer acquisition cost at $21, suddenly that attractive gross margin might actually lose money on every unit sold.

We have seen a color cosmetics brand that had stellar 85% gross margins but was struggling financially. Why? Their hero product, $22 lipsticks, had a negative contribution margin after accounting for all channel costs. Free shipping and customer acquisition costs were eroding their economics. They needed to focus on building Average Order Volume or AOV by bundling multiple lipsticks to make money direct-to-consumer, as well as looking at different packaging and shipping solutions to reduce variable costs.

The Power of Absolute Contribution Dollars

Here’s where many founders (and investors!) can get it wrong: they obsess over percentage margins without considering absolute dollar contribution.

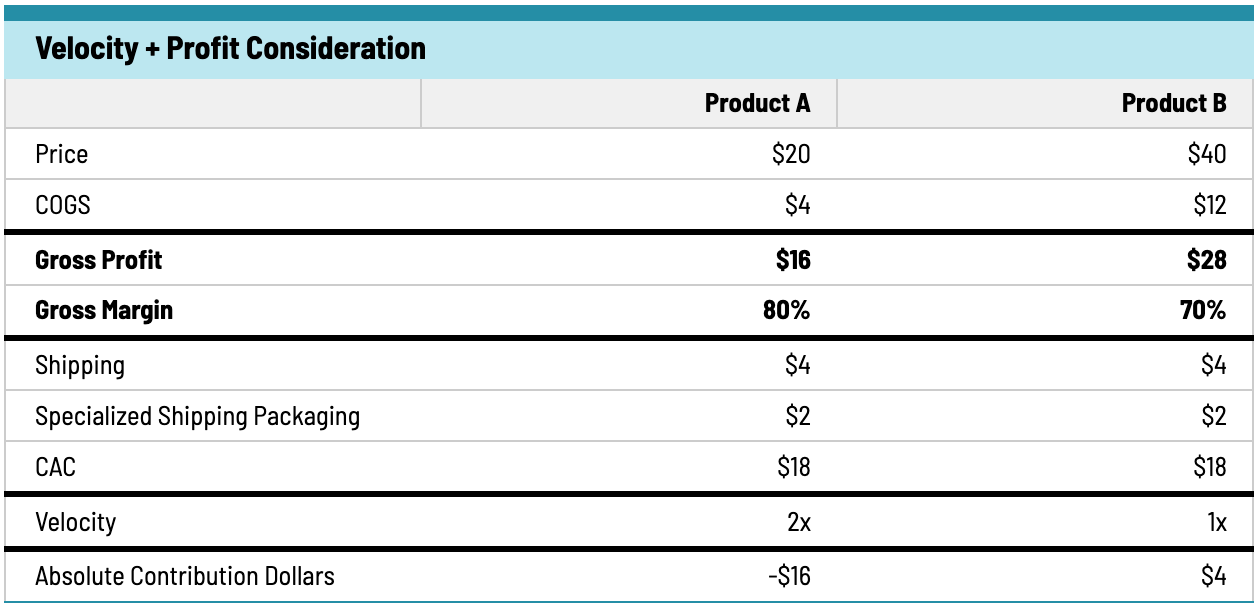

Consider these two products:

Even though the lipstick has a higher percentage margin, the tinted moisturizer contributes 1.75X more dollars to your bottom line with each sale. However, if the brand sells lipsticks at 2X the velocity of tinted moisturizers, then that product line contributes more absolute dollars. Good percentage gross margins are not the whole story. Brands need to think in units, dollars and percentages combined to craft the right economic recipe.

When building your product portfolio, balance high-percentage-margin items with high-absolute-dollar contributors, and then think about velocity. Absolute dollar contribution is what actually pays your fixed costs and eventually becomes profit that you can reinvest to grow.

Channel Economics

Not All Sales Are Created Equal

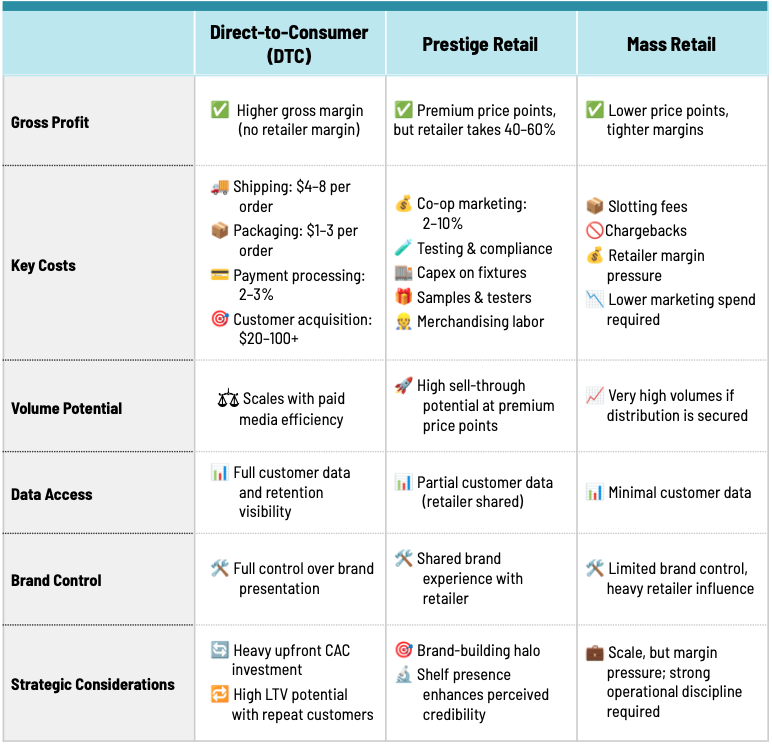

The channel through which you sell can also dramatically impact unit economics. Let’s compare:

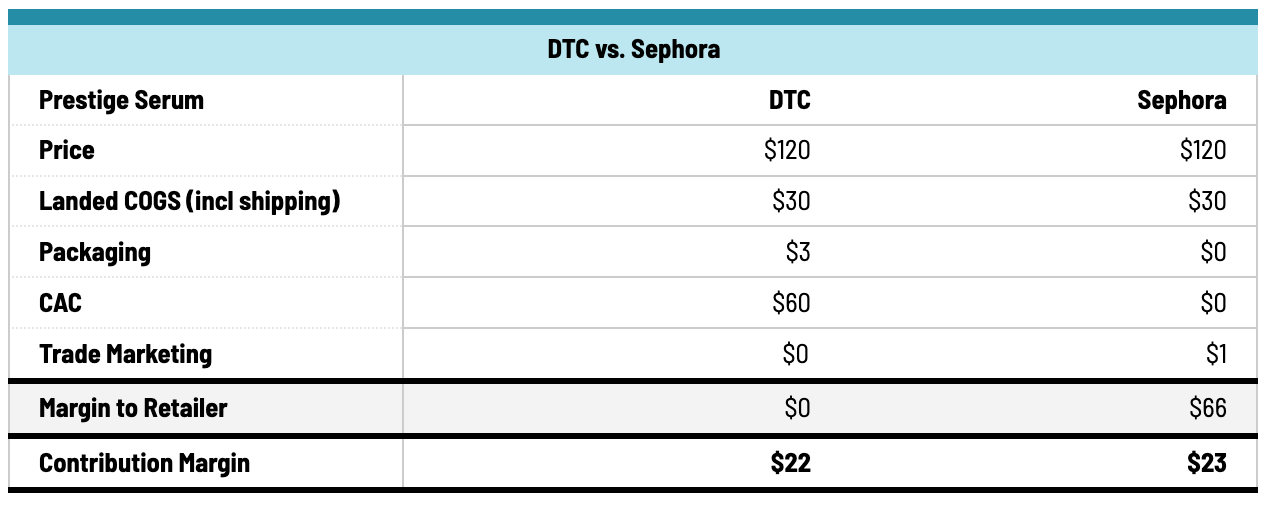

A luxury serum selling for $120 might generate $90 in revenue through your DTC site vs. $60 at Sephora. But when you factor in the $55 you spend to acquire that wealthy, high-value DTC customer, Sephora might actually deliver better unit economics.

However, Sephora might only consider carrying you if you drive a minimum level of demand on DTC and high Earned Media Value. EMV gives you a monetary value for free publicity your brand received. Tools like Tribe Dynamics, CreatorIQ and Meltwater can measure EMV. There is no automatically “better” answer here. It depends on your brand, price point, consumer mix and a myriad of other factors. What is essential is that you understand these economics at a contribution level to ensure that your strategy and tactics are structurally profitable and scalable. Too many brands are investing scarce cash behind strategies that are not economically viable.

Prestige vs. Mass

Different Economic and Operational Models

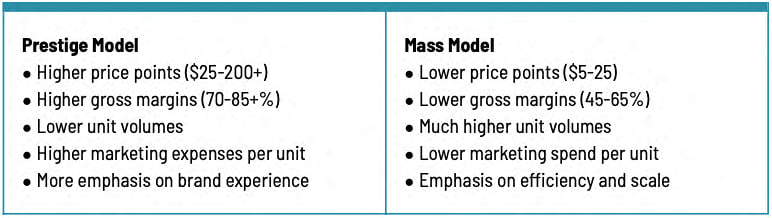

Many founders dream of building the next prestige beauty unicorn, but mass market brands can be incredibly profitable too, they just operate on a different economic model that is more about unit volume—a smaller margin times a large unit volume is still a big number:

The mass model requires productivity, operational excellence and scale to compensate for lower margins. But when executed well, the economics can be extremely attractive. Consider E.l.f. Beauty. Their average unit price is under $10, but they’ve built a billion-dollar business through operational efficiency and phenomenal unit throughput—192 million units in 2024, according to Circana.

Pricing Power

The Economic Game-Changer

Let’s run the numbers:

- A moisturizer priced at $45 with a 70% gross margin and $20 in variable costs yields $11.50 product contribution margin

- Raise the price to $50, an 11% increase, and contribution jumps to $16.50, assuming COGS and other variable costs do not increase

- That’s an additional $5.00 per unit to be invested in creating more demand or flowing directly to your bottom line

One prestige skincare brand increased prices by just 8% across their range and saw their EBITDA double. Why? Because when you’ve built genuine consumer love and differentiation, pricing power per unit creates incredible fixed cost leverage.

Final Thoughts

Beauty and CPG brands that scale successfully and attract investment analyze and own their unit economics across products, categories and channels. They know exactly what it costs to make, market and deliver each product, and they’ve structured and actively manage their portfolio to maximize overall contribution.

Run the numbers. Get granular. Challenge your assumptions about which products and channels are actually profitable. The most beautiful thing about your beauty brand should be its economics.

Written by Andrew Ross, senior advisor and venture partner at XRC Ventures’ Brand Capital Fund, this post originally appeared on the early-stage venture capital firm’s Substack, The Brand Capital Report.