What Is Blonde?: A Conversation With Tressie McMillan Cottom

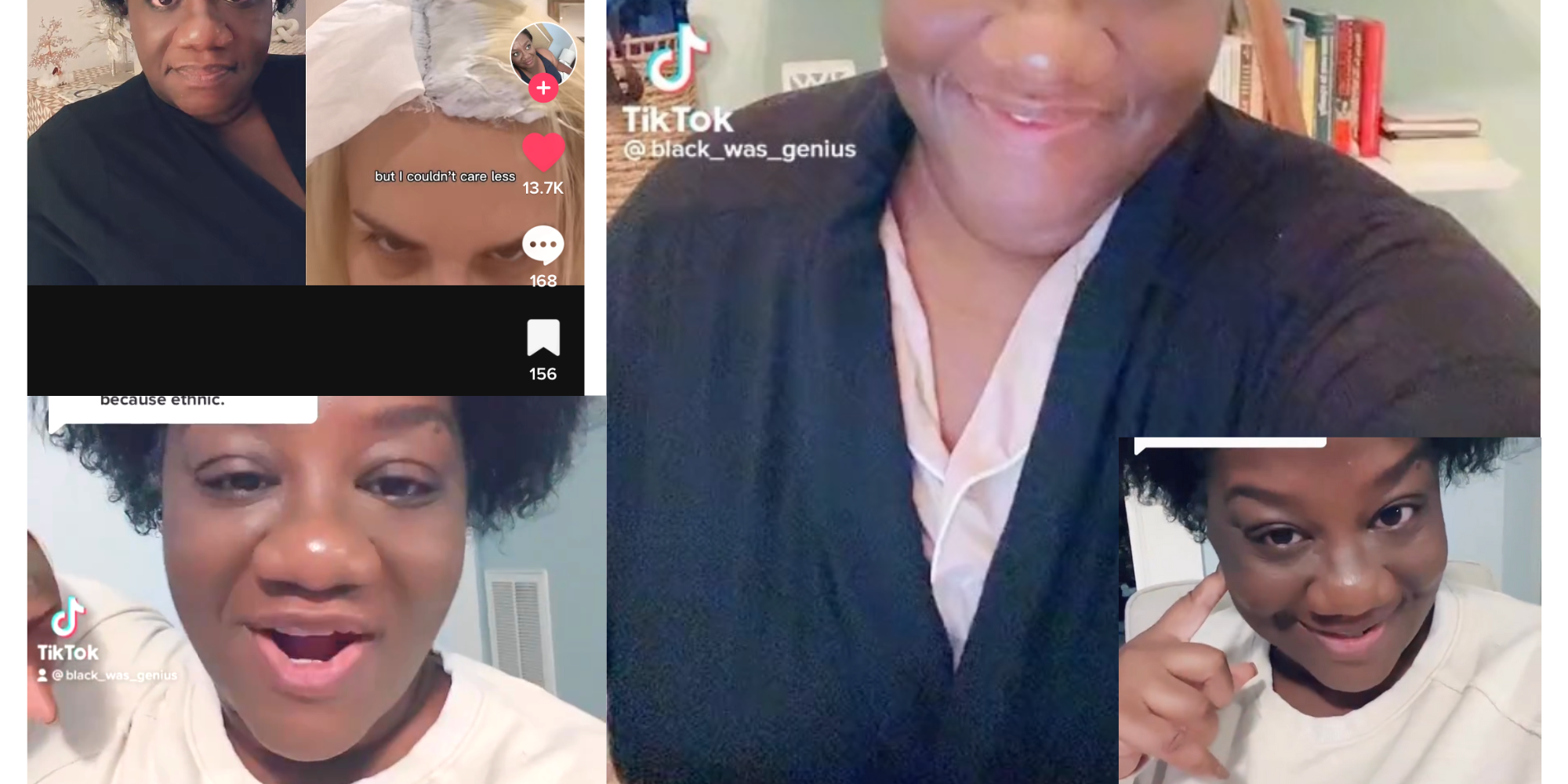

Tressie McMillan Cottom, an author, sociologist and associate professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, started 2023 off with a bang. On Jan. 1, she ignited a conversation on TikTok about the concept of blonde. “Blonde is not a hair color, it is a signifier of a type of person—and they never want to talk about that,” she says in her first TikTok video on the topic. “What kind of person is the question.”

The conversation went viral, and the video quickly racked up nearly 1 million views. McMillan Cottom posted dozens of subsequent videos responding patiently and humorously to a handful of the thousands of comments she received on it, including accusations that she must hate white people. Some comments were from people genuinely engaged in the discourse who asked questions in good faith. Others were from people incensed at the suggestion that being blonde has any racial import.

By Jan. 3, McMillan Cottom’s TikTok account was suspended. It was reinstated two weeks later, and the conversation about blonde hair didn’t end while McMillan Cottom was off the app—or since she’s been back. Creators from various backgrounds are sharing their thoughts on the political, ethical and racial implications of blonde hair.

Beauty Independent spoke with McMillan Cottom about the hierarchy of blondness, her TikTok ban, Black women’s experiences getting thrown off the platform, Dolly Parton and much more.

In your first video on the subject of blonde as a racial signifier, you stitch a creator asking her mom if she’s a “natural brunette,” and you were met with a lot of vitriol in the comments. Were you surprised by that?

No. I thought, “This is a wonderful video to encapsulate these ideas.” I was flagging it for myself and for some of the students that followed me more than anything else. Then, it became a thing, and as I was responding to it, people were definitely engaged.

These are, in my world, work-a-day ideas. It’s not stunning in the world I tend to work in to say that blonde is a racial signifier. This is not groundbreaking. In fact, I only said that high-level idea and not my angle on it precisely because I am working on a book that involves it. The idea that blonde is a racial signifier is actually so work-a-day in my world that you couldn’t write a book about that. I’m writing something a little bit more specific about how it’s become a consumer identity and a political identity.

The response was really interesting to me. I’ve been on TikTok for a few months, just hanging out in the space, but I’ve been in social media spaces, all of the iterations, for 15 years now, so I see the ways things happen. I didn’t know how sensitive TikTok’s reporting mechanism was, and I remember laughing to myself saying, “Well, I’m about to find out.” It was clear that it was like what we would’ve said on Twitter or Facebook was a swarm attack. Somebody told everybody to go report me, then I was blocked, and then I was banned and locked out.

Did you try to reach out to anyone at TikTok to reinstate your account after it was banned?

For me, this is something of a sunk-cost fallacy. How much did I want to invest in this? I’m not a “poor me.” I’m a New York Times columnist and a professor. I can speak to people. What it did say to me, however, is, what about the people who are not, right? I’ve had hundreds of people reach out to me, overwhelmingly women, obviously, mostly women of color, saying, “I’ve been banned, too. This is the thing we’re going through.”

One Black woman influencer reached out to say to me, “Listen, I’ve been banned a dozen times, mostly just as an anti-competition strategy.” Her feeling is that, when there is a white creator who basically is doing the same work, they have them ban the Black creators just to get them out of the space, which I found fascinating. There was all this talk, especially around beauty and wellness influencers, about who was allowed to legitimately own certain ideas.

I know a lot of people who follow me have reached out to TikTok, and I told them it’s certainly their right to do it. But I haven’t pursued it too hard. I’m actually more interested in it intellectually as somebody who thinks about whether or not these spaces are good spaces. I think about that a lot, what women give up to do all of this emotional labor on these apps, doing that kind of emotional labor for years and be banned and have no recourse. I’m thinking about that a lot.

I’ve thought a lot about how easy it is for women to be sort of systematically cut out of that space. They’ve been doing this Black girl follow train. They’ve been very popular, and tons of them got banned in response to that.

Is there a way to be ethically blonde?

There is this way that beauty is absolutely performative, and it should be play. Nobody believes that more than a Black woman because, who plays with beauty more? The creativity is off the charts. I see what people can do. They can literally build a new human being these days out of hair and makeup, and it’s just stunning to me. I love that.

At the same time, I know what I know about the ideas that we attach to it. So, the thing I’m always wrestling with is, what of this can we keep that doesn’t hurt? Should we develop a language for what does hurt so that we can get rid of it?

I do wish that there was [a place to have these conversations]. Obviously, I think TikTok isn’t it. If I experience this on TikTok, there are hundreds of thousands of Black women who have had that experience. I don’t want to distract from that. Also, it was clear to me from people’s authentic response that we do need a place to have this conversation. I’m just not sure now where that place is.

Is there a certain part of the conversation you started about the concept of blonde that particularly sets people off?

I think what maybe sets people off is this: There’s a moment when I said something like, “Being a natural blonde as opposed to a chemical blonde, there is a status hierarchy to that.” I think that’s it. Because that’s when people started saying, “Well, what are you saying about my babies?”

The fact that they go there says that that’s the thing that pushed their button. It was something about the biological nature of it. I think the quote-unquote natural blonde conversation gets at the root of it because that’s the part that is implicating women the most, right? So, they draw on the very thing they think is their strength, which is I’m a mother, this is my unassailable identity. That’s why I think they started bringing in their children.

You’re writing a book exploring this topic. Are there other works of yours you would recommend to people who want to dive deeper into it?

I’ve got a whole stack of books here that I’ve piecemealed over the years. I can tell you, the idea started for me as I was reading these books for other things, and they started looking like they were the same conversation. This might surprise you, when this started to crystallize, I wrote a piece about Dolly Parton, the blonde of all blondes, right?

I love Dolly Parton, but I had to think about her critically. It’s one of my favorite things I’ve written. There’s just a little paragraph in there where you can start to see the seed of this idea of blonde. I was reading all these ideas, and I thought there must be a definitive book on the history of blondness. I took for granted that somebody had written it. I looked and I sent a research assistant to look, and we couldn’t find it.

You’ve got all these books about the blonde bombshell, the history of Marilyn Monroe, of course. And I just stuck a little pin in it, I started putting books aside, but it started with my ideas about Dolly Parton.

Are there any other works you recommend?

There’s a lovely book by Sarah Smarsh [called “Heartland”]. She’s from a working class rural background, and she talks about how important it was that her mother was pretty to how her mother was able to survive. She’s like, my mom being pretty was the difference between her getting tips at the restaurant or not.

She has a thing about how much her mother invested in keeping her hair blonde as part of that performance. It’s memoir-esque, which means it’s easy to read. She gets at some of these ideas of thinking about it more than just her mom liked the look. She’s thought about what it meant, quite frankly, for their survival growing up.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.