Sex In Contemporary Beauty Advertising: Is It Liberating Or Damaging?

From the beginning of mainstream consumer products, sex has been a tool wielded to promote them. In the 1930s, AdAge documents a Listerine ad featured a nude woman’s back and her breast, and marketing for Woodbury soap is believed to include the first image of a fully naked woman used in advertising.

More than 60 years later, Nars promoted its blush Orgasm, which was followed by a lip gloss and a two-in-one lip and cheek stick called The Multiple, with pictures of women with ecstatic expressions. Yves Saint Laurent topped it in 2000 with an ad for the fragrance Opium centered on a woman wearing only accessories and touching her breast.

Since then, sex-tinged ads and products have multiplied. Tom Ford put perfumes on vaginas and cleavage for the brand’s Tom Ford for Men 2007 ad, and Marc Jacobs posed nude for his brand’s Bang fragrance in 2010. Urban Decay’s Vice lipstick line contains the shades Carnal, Morning After, and Perversion; Tarte distributes a Sex Kitten eyeshadow palette; and Too Faced has made a mint off its Better Than Sex mascara.

Indie beauty brands have joined the sex party. Heretic’s Dirty Series sells flirty scents like Florgasm; Jeffree Star Cosmetics’ imagery is populated with come-hither looks and open mouths; and Squish Beauty’s website features sensual footage of women eating lollipops and posing in underwear.

In the age of woke capitalism, modern beauty brands view their suggestive marketing campaigns as destigmatizing women’s sexuality and advancing society’s conversation about sex. But is their advertising truly enlightened or just another chapter in a long history of the commodification and objectification of women?

With Heretic’s Dirty Series campaign, founder Douglas Little explains he attempted to illustrate the centrality of sexuality to humanity. He says the imagery is grounded in the understanding that “how to give and receive pleasure is a vital aspect of living a healthy and more fulfilled life.” For similar reasons, the brand’s site posts “I am Heretic” interviews spotlighting public figures like erotic jewelry designer Betony Vernon.

In a break from the convention of women as the main targets of sexual desire in advertising, Heretic incorporates male models in its marketing. Little says, “Our fragrances are gender-neutral, and we feel that our imagery should be provocative and appeal to everyone.”

At Squish, founder and plus-size model Charli Howard emphasizes the brand’s sexual imagery lets women express themselves. She instructed her models to bring clothes that made them feel empowered to Squish’s shoot. Many brought lingerie and tight-fitting outfits on their own accord.

“The message we should be sending out is: You can look a certain way, you can be naked if you want to, you can have your boobs out if you want to, but that’s your right to do that.”

“Women should be allowed to be whatever they want,” says Howard. “The message we should be sending out is: You can look a certain way, you can be naked if you want to, you can have your boobs out if you want to, but that’s your right to do that. I would never want to stop a woman feeling she can do that or [make them feel] they have to put themselves in one category.”

Some brands contend their sexually-inclined marketing is less about advocating sexuality and more about doing justice to their products. “It’s meant to be a means of experimentation and expression, and we believe in embracing the sensuality that often goes hand in hand with beauty,” says Urban Decay founding partner and chief creative officer Wende Zomnir. “Our shade names are part of this playfulness and also embody the colors they label in some way.” She elaborates that, for example, Morning After is a nude shade that reflects how someone might look when they wake up, and Carnal is “earthy” with “a bit of bite.”

Little ties the sexuality in Heretic’s Dirty Series promotional imagery to the natural ingredients in the scents. “Nature is erotic,” he says. “The sole purpose of a flower is reproduction, so why not explore this deliciously suggestive world through a contemporary lens? Fragrance is ultimately about storytelling, and the names that I come up with are designed to convey the backstories for the fragrances. I.e., Florgasm: What would it smell like if a flower had an orgasm?”

The beauty industry has always been intertwined with sex, points out Good Vibrations staff sexologist Carol Queen. “It’s the reason why so many people freak out when very young girls wear makeup as in those ‘baby beauty queen’ pageants,” she says. “The makeup sends a sexualized message people may not register in an older teen or adult woman, but it’s extremely noticeable when it’s a little kid.”

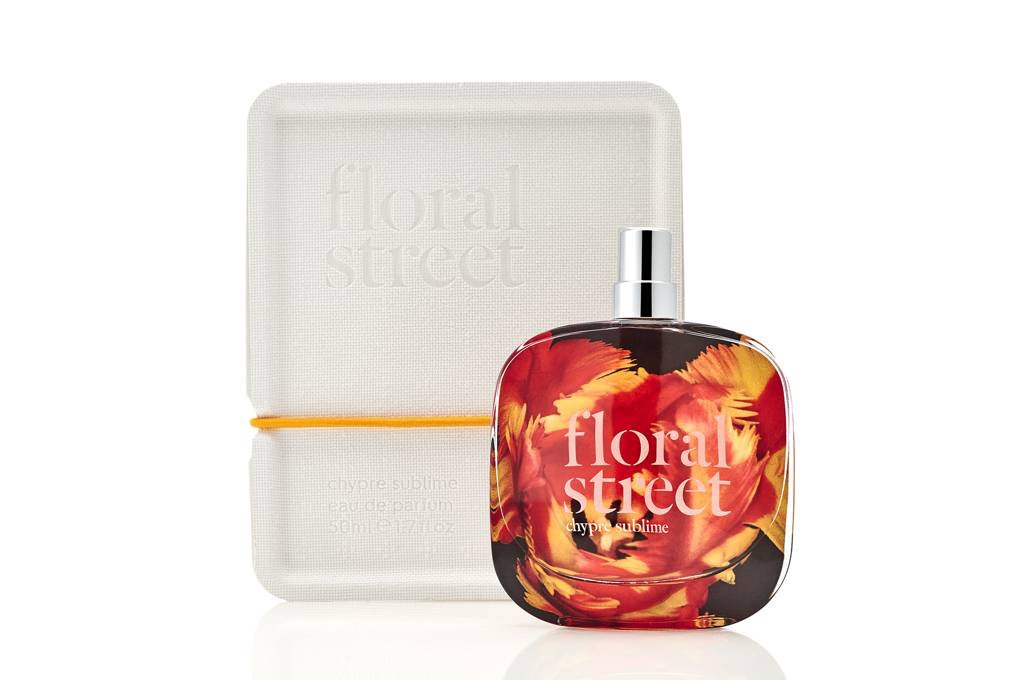

Not all beauty brands are interested in tangling their products and marketing with sex. Michelle Feeney, founder of Floral Street, isn’t relying on sexual language for describing and naming her fragrance brand’s products. “I think the word ‘sexy’ is outdated and unnecessary when it comes to describing a fragrance. We have much better words to describe how we look and feel and also to describe the many facets of a fragrance,” she says. “I am in no way saying, ‘Don’t feel sexy.’ I just think that’s a personal feeling, not something for sale.”

Feeney is conscious about avoiding objectifying women. “I feel not participating in the sex game to create attention for products is a way of rebelling against over-sexualization, particularly of women, in fragrance advertising,” she says. “I think from the 1970s until quite recently, the marketeers who have controlled the advertising budgets and creatives have relied upon the notion that women and men want to look good to feel sexy and attract others. Now, with the rise of individualism in a modern diverse age, people want to use beauty products to feel good about themselves and also express individualism, whatever the age. I feel strongly that sexualized marketing simply won’t work in the future as the lines blur on what is beautiful and attractive.”

“Sexualized marketing simply won’t work in the future as the lines blur on what is beautiful and attractive.”

The difference between objectification and confrontation of sexual taboos in marketing may have to do with whether the product at the heart of that marketing is sexual, says Queen. It’s not a stretch for products like bikini area specialist The Perfect V and Coochy shaving cream to have sexual content in their marketing, for instance. “Having sex-inflected body care products makes sense and has context in a different way than if it’s a big multi-national ‘women must always be sexy’ kind of brand,” says Queen. “I think when products are made to be safe for the vulva or vagina, they definitely should be marketed as such, but that doesn’t mean they need to be overtly sexualized either.”

Queen argues Quim, which offers a cannabis-based vaginal care line, does a good job of towing the line. “While Quim is not unsexy, it’s more understated and way less sexualized,” she says. “It says to me that this brand wants to acknowledge sex and genitals without being squeamish, but also by not reducing genitals to their sexualized image. It’s not as strongly gendered either…Very gender-heavy marketing leaves some consumers feeling unseen and left out.”

It matters who’s behind the campaigns, too, stresses Queen. Because Squish is owned by a woman—and a woman known as a body positivity advocate—the message is more likely to come off as one of self-acceptance rather than as one of oppression. The intended audience is significant as well, says Howard. “Squish isn’t designed with straight men in mind,” she says. “It’s designed for women. We’re selling to the female market. We’re not selling to men. So, if some people have got a problem with that, then it’s on them.”

Queen argues sexualized marketing becomes a problem when it “sends the message that, if you don’t conform to some outside ideal of sexiness and sexual performance, there’s something wrong with you.” She continues, “The right way doesn’t shame or narrow what’s acceptable while still giving the customer a reason to value the product.”

Howard asserts there’s a difference between depicting women as sexual and objectifying them, and it’s crucial to provide women a safe vehicle to communicate their sexuality. “Women are capable of so many things, and I think that owning your sexuality isn’t a negative thing,” she says. “I think women are great, and they can do all these different things if they want to.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Since the dawn of consumer products advertising, it’s become a popular move for brands to use sexual language and imagery in beauty marketing.

- Brands today using sexual imagery in marketing campaigns feel that they’re breaking taboos and giving women a chance to express themselves by doing so.

- A few brands explicitly avoid sex in their marketing to send the message that there is more to women that their sex appeal.

- Whether sexual imagery and language are objectifying or liberating depends on whether the product being marketing is sexual, who is behind campaigns and their intended audiences.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.