Do Founders Have To Build Their Brands In Public?

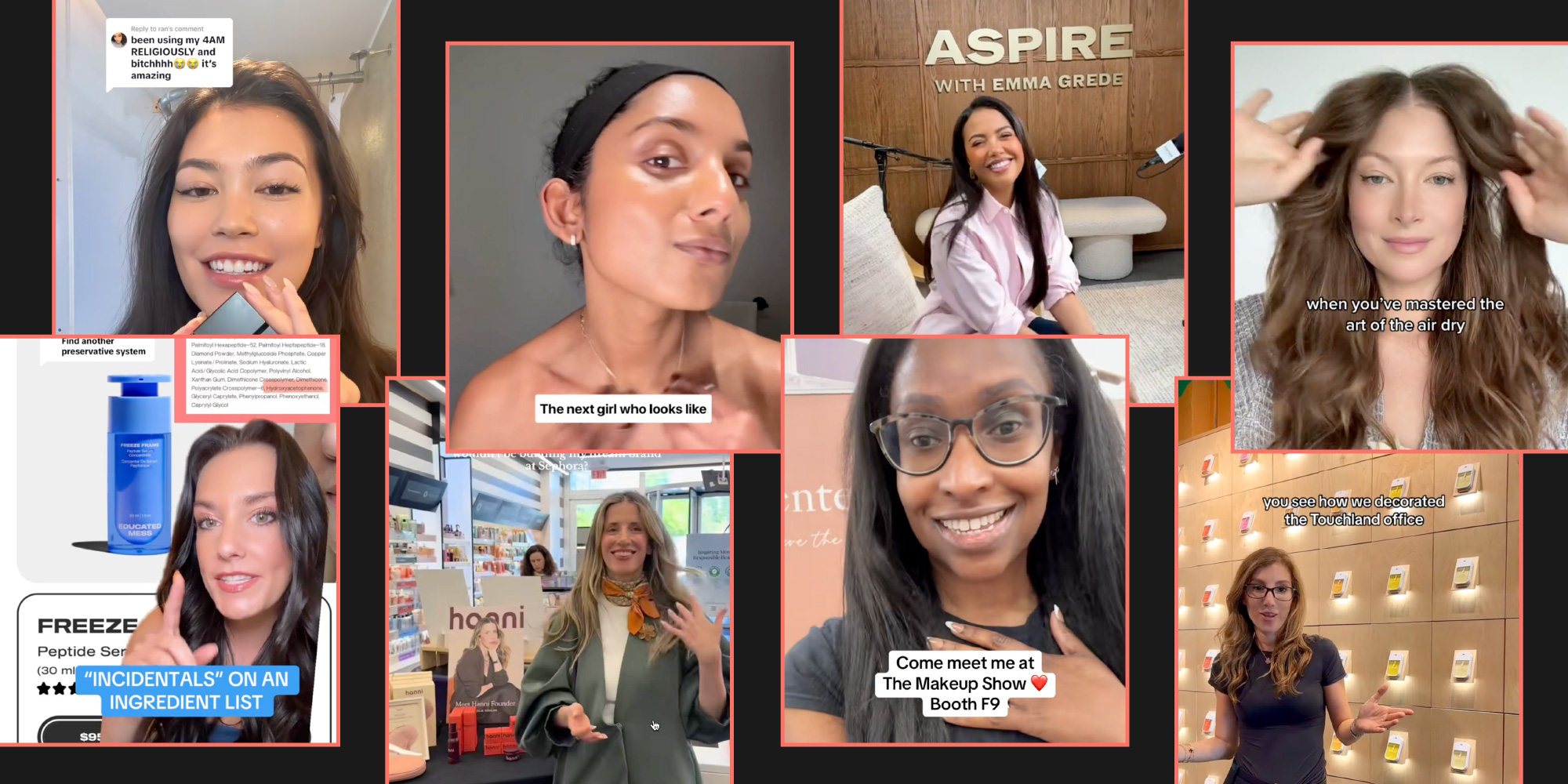

In an interview with Beauty Independent in April and a Substack post a month later, Ali Kriegsman, brand advisor, author of the book, “How To Build A Goddamn Empire,” and co-founder of Bulletin, discusses what she describes as the mounting pressure for founders to be “both an operator and an influencer.”

She told us, “It’s much harder to convert consumers without putting yourself out there, telling your story and getting them to believe in you and understand why you built the brand. Getting them bought into your energy is such a critical part of the funnel.”

Kriegsman’s Substack post was prompted by Church & Dwight’s acquisition of Touchland, which was built by Andrea Lisbona, a founder with a relatively low social media profile (she has nearly 20,000 followers on Instagram and 11,000 on TikTok). She points out that Hero Cosmetics co-founder Ju Rhyu, another talent who has entered the Church & Dwight universe, shepherded her brand without simultaneously turning content creation into a first-order job responsibility.

But Kriegsman finds there are many more examples of male founders avoiding the pressures to become influencers. She cites Danny Harris of All Yoga, Andrew Benin of Graza and Andrew Dudum and Jack Abraham of Hims. Kriegsman writes, “In a twisted way, it’s almost like the female consumer needs to believe that the woman they are buying from is ‘worth’ supporting, so by putting her front and center, the brand can check that box.”

Diving deeper into this discussion, for this edition of our ongoing series posing questions relevant to indie beauty, we asked 13 beauty entrepreneurs, consultants and investors the following: How important is it for brand founders to also be influencing on social media in support of their business? What are the upsides and downsides? How would you characterize the founder of this era of CPG entrepreneurship? Five years from now, if we were to reflect on this era of front-facing founders, what do you think we will conclude?

- Naomi Emiko Co-Founder, TNGE

The TL;DR is: Not every founder needs to be an influencer, but every founder needs a narrative. In a low-trust, low-loyalty and content-saturated market, consumers are no longer just buying products, they want to buy into your belief system. So, if founders are not telling their story, someone else will fill in the gaps.

We do, however, need to apply some much-needed nuance here. Founder-as-influencer has become quite the growth hack, but, in beauty, it's also a gendered burden. We've come far with regards to gender fluidity in branding and marketing, but, in reality, male founders often get to remain the architect. Female founders, however, are still silently expected to become the avatar.

Yet, we've seen numerous extremely impressive brand growth stories, where female beauty founders kept a low profile on social media. The narrative though still is that the algorithm loves a charismatic woman selling her transformation arc, and that seems to be the only way forward if you're building a brand.

But it's long overdue that we create a new archetype for this era. The inflationary use of "girlboss" does limit the freedom of expression as a female founder because there's so much definition attached to it. The same goes for "founderfluencer.” It almost denies you to be original because there's so much best practice circulating that you need to apply.

I would love to see a term such as “cultural engineer,” meaning she's not just building a business, but she’s curating cultural relevance in real time. She’s strategic, media-literate and knows how to deploy visibility without becoming a content farm of one.

Five years from now, we’ll look back on this moment as a correction era. Founders will have tested the limits of parasocial branding, and the smart ones built modular visibility, appearing with precision, not pressure. And the same goes for influence: It will be redefined not by volume of content, but clarity of conviction.

- Amanda Pond Founder and CEO, MOD Consulting

It’s increasingly important, but not always essential, for brand founders to have a visible presence on social media, especially in beauty and CPG, where storytelling and emotional resonance drive purchasing behavior. Founders who are also content creators can forge direct, trust-based relationships with consumers, humanizing the brand and accelerating loyalty.

The upside is powerful. Authenticity becomes a competitive edge, and the founder’s personal narrative can often break through algorithmic noise in ways that polished brand content can’t. But the downsides are real: Burnout, blurred boundaries between personal identity and business, and the pressure to constantly perform can undermine both mental health and strategic focus.

The founder archetype of this era is less “girlboss” and more “narrative architect.” This term acknowledges that the modern founder doesn’t just run the business, they shape its cultural context.

Whether through behind-the-scenes TikToks, long-form thought pieces or candid Reels, today’s founders are tasked with curating a compelling brand universe that resonates across fragmented digital channels. The term “narrative architect” feels relevant because it values strategic storytelling over performative hustle and makes room for both visible and more private leadership styles.

Five years from now, we may look back on this era and recognize both its creative innovation and its unsustainable demands. We’ll likely see a correction with more balance between public presence and operational excellence and perhaps a move toward collective storytelling, where teams and communities carry the brand narrative alongside or instead of a single face.

We might also reflect on the gendered expectations placed on women founders to be both brand and spokesperson and push for more equitable visibility standards across the board.

- Hana Holecko Strategic Innovation Consultant

There’s a difference between being influential and being an influencer—and we’ve blurred that line too much in beauty. As a former founder who personally created all of my brand’s content, I can say from experience that trying to build a company and a public persona simultaneously is often unsustainable.

I never had a desire to be an influencer. I didn’t want to perform myself. And, yet, I often felt that, in order for my brand to succeed, especially as a woman, I had to be seen, not just as a founder, but as a personality.

Ali Kriegsman articulates something I saw firsthand—there’s an added burden on women, especially in beauty, to justify their existence through constant visibility to “earn” the consumer’s support by being relatable, inspirational and aspirational all at once.

Kriegsman is right that expectation doesn’t exist evenly across genders. I did some research, and men make up 75% of funded DTC founders, but contribute just 42% of branded content, according to a 2023 Cartograph report.

The pressure is intensified by data that marketers often cite. Beauty shoppers are 3X more likely to purchase from a brand whose founder they follow on social media, and 63% of consumers trust influencers more than ads. So, when founders act as influencers, it’s seen as a CAC-lowering strategy, not just a branding decision. But the personal cost can be immense.

That said, I do believe influence is critical to building a modern CPG brand, but the influence doesn’t have to be embodied in the founder. It can come from community, clinical proof, third-party validation or exceptional product storytelling. In fact, a YPulse report found that, while 83% of gen Z shoppers want to support brands aligned with their values, only 37% say those values must come from the founder.

If we reflect five years from now, I think we’ll see this as the “visibility era,” one where brands rose and fell based on a founder’s ability or willingness to perform. I hope the next era makes room for what I’d call the “builder founders,” operators who influence through ideas, infrastructure and integrity, not just personality. And I hope consumers, investors and media start asking not just who is on screen, but what they’re building offscreen, too.

- Cristina Nuñez Co-Founder and Managing Partner, True Beauty Ventures

At True Beauty Ventures, we have seen all kinds of successful founders: the magnetic storytellers who thrive in the spotlight and the operational builders who let product and brand equity speak louder than their own presence. Both models can work. What matters most is authenticity, leaning into your strengths and building the right team around you to scale what you do not want or cannot afford to do yourself.

Today’s founder is often expected to be both operator and influencer. That can be a strategic advantage, but it is not a requirement. When founders are naturally able to engage audiences and build community, it unlocks more capital-efficient growth through organic traction. But it has to be real. Consumers can spot inauthenticity a mile away.

In beauty, female founders often step into the spotlight not necessarily because they need to prove themselves more than men, but because they are their consumer. They created products to solve real problems for themselves and others. Demonstrating product efficacy or sharing their journey feels intuitive, and it moves the needle.

That said, there are risks to being consumer-facing. Investors are not just backing a business. They are underwriting a personal brand. One wrong post or public misstep can break momentum just as quickly as it built it. It is a high-reward, high-risk reality that founders, especially women, navigate daily.

I have never liked the term “girlboss,” and, frankly, I am so glad that era is behind us. I do not think we need a new label. Founders have always been creators. It is just that the definition of “creator” has expanded.

Today’s founder-creators are brand leaders who influence in many forms. They blend storytelling with strategy, and they know when to step into the spotlight and when to let the product speak for itself.

Five years from now, I think we will look back and realize the strongest brands were not built on founder charisma alone. They were built on substance, strategy and the kind of execution that happens both in front of and behind the scenes.

- Lynn Power Founder and Co-Founder, Power Beauty Collab and Masami

We have the conversation about how much a founder should promote themselves on social media often within the PBC. The reality is that some businesses benefit from a strong founder story more than others. If the founder created a product that is intrinsically linked to their own story, it's hard to avoid telling that story.

But some people are just not comfortable being on camera—and that shows. It's better for them to find a different medium like writing. Women and female founders are also judged much more on their looks on social media it seems, especially in the beauty biz. If you're young and attractive, you've got a much easier chance at getting noticed in a positive way.

But I think there's generally more upside than downside in finding your unique way to build your personal brand. It will halo onto your business and help give you authority and credibility. Who wouldn't want to work with a badass woman?

- Benjamin Lord Founder, Antidote

The founder-as-influencer discussion has become oversimplified into a binary choice, when it should really be about strategic alignment between founder personality, distribution channels and sustainable business models.

Distribution-Dependent Strategy

Founder visibility requirements are intimately connected to your chosen distribution model. The most successful brands make this choice deliberately rather than following industry trends. EltaMD's dominance as the No. 1 sunscreen on Amazon demonstrates that exceptional products with strong search optimization and media funnels can build massive market share without any founder presence whatsoever.

Conversely, brands betting heavily on TikTok Shop, Instagram Shopping or direct-to-consumer models often require founder authenticity to cut through algorithm noise and build consumer trust. The key insight is that neither approach is inherently superior. They're different strategic paths requiring different founder skill sets and comfort levels.

The Strategic Operator Approach

Rather than the "girlboss" terminology, I'd characterize today's most successful beauty founders as "strategic operators," entrepreneurs who make deliberate choices about their public presence based on business objectives rather than industry pressure or personal ego.

This includes founders like those behind EltaMD who built systematic growth engines focused on product excellence and channel optimization. It also includes highly visible founders who use personal influence strategically to access distribution channels that would otherwise require prohibitive marketing budgets. The common thread isn't visibility level, it's intentional decision-making about how founder energy gets allocated.

Personality-Business Model Alignment

The most sustainable approach requires honest self-assessment. Some founders thrive on content creation, public speaking and community building. For them, founder-influencer strategies can be genuinely energizing rather than draining. Others prefer product development, operations optimization and behind-the-scenes growth. Forcing these founders into constant content creation creates burnout and often produces inauthentic content that fails anyway.

The smartest founders audit their natural strengths and build distribution strategies accordingly. A founder who loves being on camera might prioritize TikTok Shop, podcast appearances and a trade show presence. A founder who prefers systematic approaches might focus on Amazon optimization, programmatic advertising and retail partnerships.

ROI Reality Check

Measurable returns are crucial. A founder spending 20 hours weekly creating TikTok content might generate impressive engagement metrics, but struggle to trace direct sales impact. Meanwhile, that same 20 hours invested in Amazon listing optimization, supplier negotiations or Criteo campaign management often produces clearly measurable revenue increases.

The most sophisticated founders track content ROI as rigorously as any other marketing channel. If founder-generated content isn't producing better customer acquisition costs than paid alternatives, it's a strategic mistake regardless of engagement rates or industry expectations.

Gender-Neutral Strategic Choice

This absolutely isn't a gender issue, it's a personality-strategy alignment challenge. Some male founders love the spotlight and excel at building personal brands that drive business growth.

Some female founders prefer focusing on product innovation and systematic growth engines. The most successful entrepreneurs of both genders make choices aligned with their strengths rather than conforming to perceived industry expectations.

Five-Year Retrospective Prediction

Looking ahead, I believe we'll conclude that this era separated founders who understood strategic optionality from those who followed trends without considering fit. The winners will be those who made deliberate choices about public presence based on distribution strategy, personal sustainability, and measurable business outcomes.

We'll likely see two distinct paths to success: highly visible founders who built authentic personal brands that efficiently drove customer acquisition and systematic operators who built scalable growth engines through product excellence and channel optimization. Both approaches will have produced category leaders.

The founders who struggled will be those who felt pressured into visibility strategies that didn't match their personalities or business models, or, conversely, those who avoided all founder presence when their distribution channels required authentic personal connection.

Ultimately, the most important insight from this era will be that sustainable CPG success requires aligning founder strengths with distribution requirements and making strategic choices based on measurable outcomes rather than industry pressure or social media trends.

- Jennifer Lacenera Founder, Jennifer Lacenera Consulting

I’ve had the privilege of working alongside some of the most visionary female founders—Jamie Kern Lima (IT Cosmetics), Poppy King (Lipstick Queen) and Amy Lou Ford (Hello Sunday SPF). What always sets them apart is their passion and their ability to tell their story in a way that builds deep, engaged communities.

Today, being a front-facing founder with a strong digital presence is just the modern evolution of DRTV and infomercials. Only now, it’s happening on TikTok, YouTube and Instagram. It’s still about knowing your audience, showing up authentically and building trust through storytelling.

Founders know their brand stories better than anyone. And in an age when beauty consumers—especially millennials and gen Z—demand transparency and purpose, visibility can be a real growth driver. One reason women may excel in this space is that research has consistently shown higher levels of empathy among women.

When a founder combines that empathy with storytelling, a deep understanding of their customer and a smart digital strategy, they’re not just marketing a product, they’re building a brand people want to be part of. That empathy drives product innovation, responsiveness to feedback and a progressive approach to business that drives smarter decisions and more meaningful brands.

That said, there’s mounting pressure on founders to not only lead the business, but also act as its most visible marketer. They’re expected to set strategy, manage operations and simultaneously create content that performs across constantly shifting platforms.

For many, being on camera doesn’t come naturally. And in a saturated market filled with celebrity and influencer-led brands, breaking through the noise requires both volume and strategy to maintain brand longevity.

The upside? Lower customer acquisition costs, more authentic content to fuel brand awareness and less reliance on expensive influencer partnerships—huge advantages for early-stage brands working with tight budgets. But the expectation that founders must also double as full-time creators isn’t always sustainable, and it’s not always the most strategic use of their time or talent.

We’re in a digital era where we are seeing a rise of empathetic leaders, more human and more connected. Five years from now, we’ll look back on this moment as a turning point, when leadership became more human. When empathy, transparency, mission and trust became just as important as product and performance. And the winning formula for brands wasn’t innovation alone, it was turning connection into conversion.

- Rebecca Bartlett Principal and Creative Director, Bartlett Brands

There is no denying that we are in the moment of the front-facing founder, where their visibility is a growth strategy and their personality is often the brand’s source of trust and emotional connection to their consumer.

Here’s a different POV based on Bartlett Brands’ experience creating brands alongside all different types of founders and reinvigorating brands that have had to extricate themselves from their founders over time.

First, here are some successful founders you probably don't know: Alice Li, founder of First Day, her deeply personal “why” drives a clear brand and product strategy. Meg Pryde, founder of Brandefy, seeks to right an injustice for the consumer. Annie Jackson, founder of Exa and Credo, saw an actual white space.

The behind-the-scenes founder brings a different kind of strength, vision and longevity to the brand and business. When a founder remains in the background, it can create space for the brand to serve the right audience, especially if that audience doesn’t see themselves reflected in the founder’s identity.

Their role is less performative and more foundational to the DNA of the brand, allowing the brand to speak for itself and evolve with the times, with products that build authority through substance rather than spotlight.

They say, “People don’t change,” but brands must constantly evolve to remain relevant. In five years, we’ll conclude that the most successful brands didn’t rely solely on a front-facing founder to be the brand, but instead embedded a story and value system that can grow and evolve independently.

- Nigar Zeynalova CMO and Beauty Strategist, Spark Edit.

After years in big beauty, I shifted to working with small and midsize brands, and that’s where I truly see the power of founders. Every brand I led had a strong founder story, and it became one of the most valuable tools for building emotional connection with consumers.

One of my earliest experiences was a panel event with the co-founders of 100% Pure in front of our retail store at Santana Row. The turnout was incredible, but what struck me most were the customers. They didn’t just use the products, they knew everything about our founders: How they started, their dog’s name, even the very first product.

After the panel, the store sold out in under two hours. The buzz online was immediate. That wasn’t just a marketing win, it was emotional velocity. That’s when it clicked: Founders don’t just build formulas, they build relationships and inspire others to take a bold move they once did.

The Upsides Of Founders Showing Up

- Emotional resonance: Consumers see themselves in founders and become emotionally invested.

- Retailer appeal: At Sephora and Ulta, I often heard, “We want to meet the founder. Can they be part of the pitch or the story?”

- Brand vitality: A charismatic founder injects soul, energy, and credibility.

The Trade-Offs Of Front-Facing Founders

- Bandwidth: Founders are already leading operations, product and strategy. Being the face adds another layer.

- Brand dependency: If a brand becomes too centered on a founder, acquisition or leadership transition becomes riskier.

As we look ahead, I believe we’ll see founders evolve from storytellers to industry catalysts, not only driving marketing for their own brands, but mentoring the next generation of entrepreneurs. They’ll become guides, educators and community leaders. T

The founders of Beekman 1802 are a great example. Not only are they a fun, energetic marketing force for their brand, but their book, “G.O.A.T. Wisdom: How to Build a Truly Great Business,” proves how founder knowledge can be scaled far beyond one company.

So, how would I describe the founder of this era? Not a “girlboss.” That term feels limiting and outdated. I prefer the magnetic operator—visionary, emotionally intelligent and willing to show up authentically when it matters. Five years from now, we’ll look back at this era and realize that founder visibility wasn’t just a marketing tactic, it was the foundation of a new, more human way to build and lead.

- Garima Ahluwalia Founder, Joly Beauty

The question before the question of how important it is for a founder to be an influencer is, how critical is community as part of the brand’s growth strategy? To expand on that, some brands are solving a problem for a community and therefore rely on early adoption and feedback from the same community. This is when it becomes critical for the founder to passionately call on the people facing a similar problem.

Another scenario is when the circumstances are such that the founder is uniquely positioned to be the brand influencer. Their background, prior achievements (plastic surgeon, scientists) extend street cred on the brand by association.

Many a time, bootstrapped beauty founders find it cost effective to take to the microphone for brand building and storytelling. In current times, when the world is divided on various issues, often customers look for brands projecting similar values. Who is a better value communicator than the founder?

As somewhat of an exception to this rule, lifestyle brands, luxury brands and super innovative brands with quality informational content can sometimes get away with limited founder influence.

The upside of being the founder influencer is a 100% creative control over the storytelling, while freeing up resources for other projects. The downside is the risk of fallibility. Founders are human and their unintentional missteps can negatively impact the brand in the current cancel culture.

The 2025 CPG entrepreneur is a versatile doer that can wear multiple hats of an operator, brand evangelizer, social charmer. It’s less about being the boss, more about rolling up your sleeves no matter what.

I am curious to see how this role evolves given new AI tools for content creation and shifting consumer buying behaviors. Regardless, as long as social platforms are battlegrounds for brands, the founder will have the critical role to influence, in some capacity or the other.

- Inna Tumarin Founder, CEO and Creative Director, Glazed Gloss

In today's digitally driven landscape, consumers are increasingly discerning, seeking to understand precisely where and with whom they invest their resources and time. These astute contemporary consumers demand to comprehend the genesis of a product, the provenance of its constituent ingredients and the narrative best articulated by the brand's founder.

It is therefore vital for founders of emerging brands to adopt a forward-facing stance, embodying the very essence of their brand and fostering a genuine, personalized connection with each patron. The archetype founder in this consumer packaged goods era must possess dynamism, thoughtfulness, approachability, substantive industry acumen and serve as the unequivocal heart and soul of their enterprise. This duality will ultimately determine the prosperity, or the demise, of your brand.

The challenge I personally confronted, fulfilling both the founder and CEO roles within my former company Global Nourish Skincare, a brand I launched which I’ve recently exited, was the inherent bifurcation of those personas, a juxtaposition that often induced a state of mental and emotional whiplash.

The founder must be amiable, relatable and readily accessible, whereas the CEO is invariably subject to decisions that may not garner universal approval, may not evoke immediate relatability and is perennially consumed by a relentless workload. The founder likewise dictates the brand's cultural milieu, which must organically emanate throughout the brand's ethos.

The most insightful perspective on a brand's culture often resides within its employees. Consequently, I discovered immense value in integrating the entire team into the process of conveying the brand's narrative. This approach assumed an independent vitality, empowering the creative team to cultivate a profound sense of ownership over the brand, which resonated authentically with the consumer.

In retrospect, five years hence, I anticipate that this era of the front-facing founder will be defined by the maxim that a founder is, in essence, the embodiment of their brand and its entire creative aesthetic, brand culture, authenticity, and that consumer perceptions are a direct reflection of the founder's essence.

As a founder, I continually reflect upon the timeless sentiment that, "People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel." We are not merely purveying inanimate objects encased in jars, we are curating a feeling, a lifestyle, a tangible outcome and a holistic experience.

- Laura Belsley Retail Strategy and Growth Expert, Constellar Consultancy

There's more than one way to slice the pie, but brands need to be intentional about how each slice supports long-term brand equity, not just short-term sales. A founder's digital presence is increasingly valuable, but not essential. Brands that solve real problems with standout products and exceptional storytelling can succeed without a front-cover founder.

Consumers crave authenticity, but founder visibility should align with personal comfort and overall growth strategy. Forced content feels awkward, distracting and may even hurt sales. Sometimes, founders are most powerful behind the scenes as they build their dream.The upside is trust and connection. When consumers see a real person behind the brand sharing the why, not just the what, it creates emotional buy-in that's hard to replicate. It also opens up opps for media, partnerships, investors, retailers and organic content.

The downside is it’s unsustainable for many. Not every founder wants or is wired to be in the spotlight. The pressure to constantly perform online can lead to burnout, blurred boundaries and distorted success tied to engagement metrics instead of business fundamentals.

There's a shift away from the performative, hyper-individualized “girlboss” archetype. Relational architect founders are moving toward a more nuanced, systems-aware leadership style, one that’s rooted in collaboration, emotional intelligence and long-game thinking. They know when to step forward and when to delegate the spotlight.

I think we'll look back on this time where founder visibility functioned as both a key growth hack and pressure cooker. Perhaps future founders can rely more on community and creator networks to shoulder the storytelling burden, so they can step back to keep building sustainable brand legacies.

- Rohit Banota Founder, Jump Accelerator

The answer, like almost everything, is it depends on whether you are a bootstrapped or funded brand. If you cannot afford to advertise, hire influencers for reach or lack strong brand distinctiveness/differentiation for engagement and conversion, it makes total sense to put yourself out there as it can compensate for both distinctiveness (since every person is unique) and authenticity, leading (likely) to higher engagement and revenue.

The upside is you save on cost and build an authentic connection. The downside is scaling will still require a lot of time investment and money as organic content can totally work, but with a speed limit.

For a funded brand, money might not solve everything, but it can make a solution affordable. If an indie beauty brand has the money to advertise and get reach, then the founder has four factors to consider:

- Put yourself out there for organic reach and use authenticity in paid and organic campaigns for hopefully higher engagement and conversions.

- Founder's comfort level, personality and desire to do so.

- Venture's need for cash flow and profits driven by high cost of consumer acquisition.

- Factoring the above, in the end, the founder has to evaluate whether it's worth it to be the face of the brand as the paid campaigns will likely far exceed the returns on organic content, and a simple A-B testing can reveal if paid works better with the founder's face/story or without for the ultimate goals.

If there is a strong need to lower the CAC, then the founder can compare an organic strategy versus paid and organic still can be with the face of the founder or without. Finally, if the founder is willing, and the founder resonates with the audience for higher performance at top-mid funnel versus without the founder to lower the CAC for both organic and paid, then the founder can finally weigh the cost-benefit versus spending more time on scaling the business.

In the case of a well-funded startup, a front-facing founder can be a risk mitigation strategy for uncertain CAC for brands with risky cash flows and low profitability.

My recommendation: Think about an organic consumer acquisition strategy/advocacy first to improve the cash flow, reduce CAC and improve profitability. Then, you can use the above four factors to decide whether the founder needs to be front-facing or not.

I would call these front-facing entrepreneurs “frontline founders” as they don't only work behind the scenes.

Five years from now, it will depend on how well AI avatars of founders can form authentic connections, assuming people in society will get lonelier. If they can, we will view today as just the mere beginning of front-facing entrepreneurs, with the practice magnifying 10X to create authentic and engaging conversations in an ever-alienating society.

If the AI avatar of the founder fails to replace the authentic human connection, then we will view today as the foundational step toward a movement for frontline founders, who start playing a bigger role in the lives of the alienated human, a consumer of content and products.

If you have a question you'd like Beauty Independent to ask beauty entrepreneurs, consultants and investors, please send it to editor@beautyindependent.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.