Why Mid-Market Beauty Brands Struggle To Secure Funding

The beauty ecosystem has a funding gap problem.

Often referred to as the “missing middle,” the gap describes the stretch between early-stage venture capital and late-stage private equity, when brands are still proving economics, scaling distribution and beginning to turn profitable. Globally, these brands tend to be in the roughly $17 million to $115 million revenue band: too big for seed-stage investors, not quite de-risked enough for large buyout funds. The result is consistent across markets—brands with traction struggle to scale, and investors can miss out on high-potential deals—but the dynamics vary by geography.

At Beauty Independent’s Dealmaker Summit, which ran from Nov. 17 to 18 in London, publisher Nader Naeymi-Rad moderated a panel exploring how the “missing middle” manifests particularly sharply in Europe. “When you’re a VC, you’re getting in early, you’re getting a good valuation,” he said. “The problem is you’ve got to wait a lifetime to exit and get what they call the liquidity.”

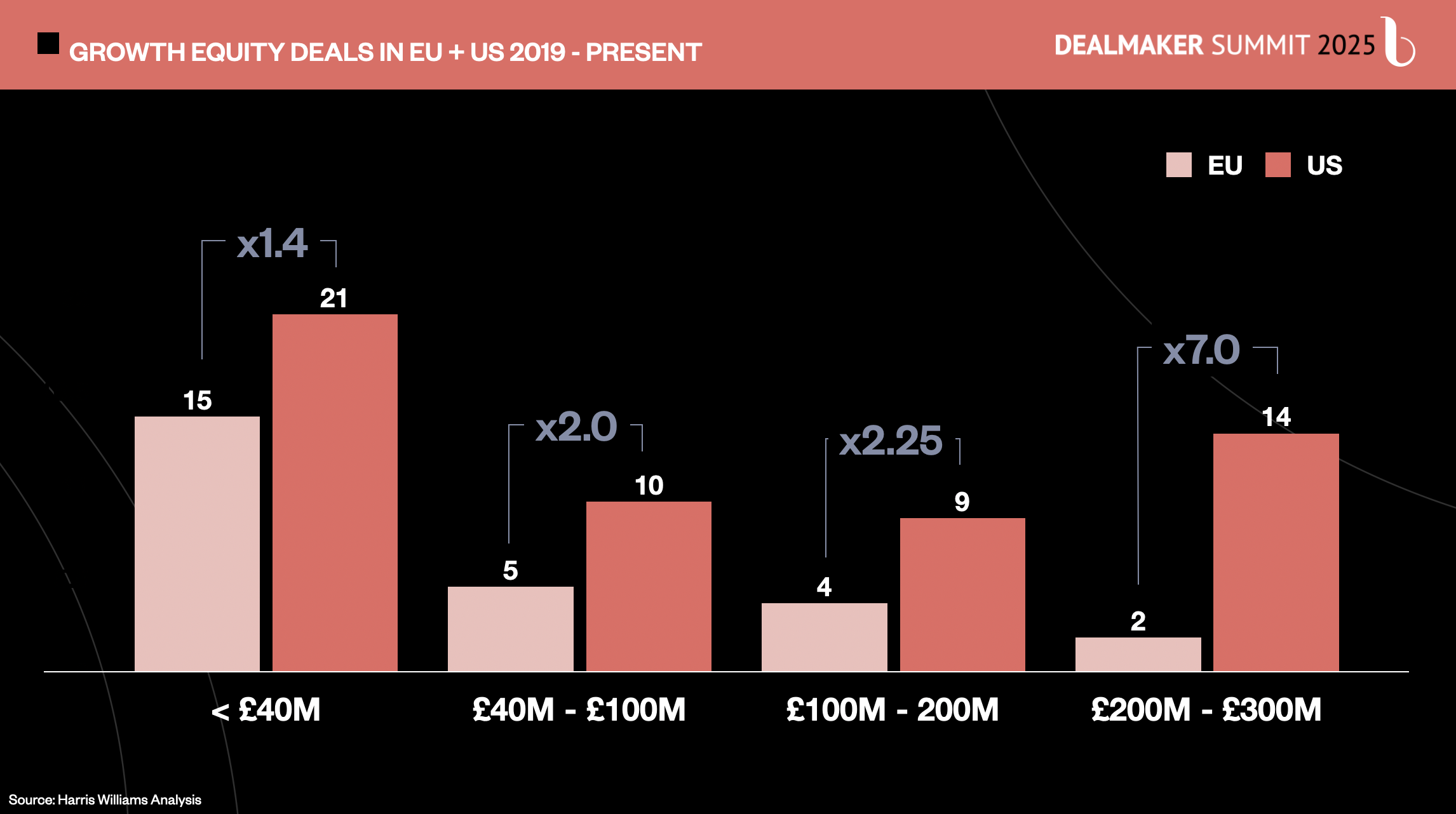

Panelists Laurent Droin, partner at Felix Capital, Jeremy Zucker, VP at Harris Williams; and Olivier Garel, managing partner for Unilever Ventures, discussed what it might take to build an ecosystem that better supports brands through this pivotal growth stage. While middle-stage challenges exist in the U.S. and Asia as well, Europe’s structural factors make the gap wider there. According to Harris Williams data, Europe trails the U.S. significantly in deal activity in the $230 million to $350 million range, only about a seventh of U.S. levels.

Zucker pointed to fragmentation as a core driver. Europe, he reminded attendees, is a collection of markets rather than a unified one. “Europe has the talent, it’s got the supply chain. What it doesn’t necessarily have is an accessible total addressable market,” he said. “We operate in a patchwork of countries—multiple countries, different languages, fragmented distribution. The U.S., by contrast, is a hegemonic market that can more easily be addressed. That offers a level of simplicity you wouldn’t necessarily find in Europe.”

He added that generalist European funds have pulled back from consumer packaged goods over the past five to 10 years. “With LPs, it’s an opportunity cost,” he said. “I could invest in consumer, but I could also put it in tech, I could also put it in industrials where I might have greater business resilience, long-term contracts and more security.”

Although the panel focused on Europe, similar pressures exist in the U.S. beauty and consumer space, where funding and M&A activity tend to cluster at the very early and very late stages—seed and Series A on one end, large private equity and strategic acquirers on the other—leaving a band of growth-stage brands with eight- to nine-figure revenues competing for a relatively thin pool of capital.

Despite the challenges, panelists emphasized that the missing-middle stage remains one of the most attractive pockets in beauty investing globally. Garel noted that it offers a more balanced risk-reward profile compared to early-stage venture, with brands more stable, more proven and often profitable. “You can still get businesses that go from 15 million euros to 100 million euros [$17 million to $115 million] of sales in three to four years,” he said. “You are protected on the downside and you have a similar upside to venture.”

Another draw is the competitive landscape. As generalist funds retreat from consumer, specialist investors and family offices have more room to operate. Mid-market growth check sizes are adjusting downward, and deals that would spark bidding wars in the U.S. may see only a handful of bidders in Europe.

Zucker remarked that investors establishing mid-market track records now will shape capital flows for the next decade. “The more that people like them have to build a track record, the more likely you’ll see growth capital flow,” he said.

Droin commented that approximately 40% of Europe’s growth-stage deals currently involve American funds. For European companies, engaging U.S. investors early can be strategically advantageous, especially because the U.S. market still plays an outsized role in determining a brand’s ultimate scale potential. “It’s maybe a very good opportunity if you are a European brand launching in the U.S.,” said Droin. “Because that’s the market you need to conquer after a certain stage.”

Still, the panelists noted that the U.S. is not the only path to success. “There are very successful, profitable businesses in Europe that you can sell only doing business in Europe,” said Garel. Yet he acknowledged that the upside of the U.S.—the world’s largest beauty market—is undeniable. “If you have the potential of the U.S., you try to keep it fully,” he said.

Droin pointed to Medik8 as a brand that didn’t scale quickly in the U.S. yet still achieved a strong exit. He said several fragrance brands are following similar trajectories. “Those brands keep the discipline and continue to have a reserve for future growth in the U.S. market,” he explained. However, he emphasized a broader truth that applies globally: “If you want to deliver outstanding return as a venture capitalist on a beauty brand, let’s be clear, the U.S. is the launch pad to deliver those kind of extreme returns potentially.”