How To Properly Test For Product Safety

Before a cream, cleanser or serum goes to market, testing it for safety is an important step to ensure it isn’t dangerous and protect brands from potential lawsuits down the line.

After all, product safety is top of mind for regulators and consumers. As Nader Naeymi-Rad, co-founder of Beauty Independent parent company Indie Beauty Media Group, explains, if a product claims to hydrate your skin and doesn’t, that won’t necessarily get brand founders in trouble, but, if a product gives a customer a rash or ends up burning their skin, “that’s absolutely a no-no.”

Last week, Naeymi-Rad moderated an In Conversation webinar episode on the science of beauty sponsored by Codex Beauty Labs with the participants Craig Weiss, president of CPT Labs, Raja Sivamani, a dermatologist and Ayurvedic practitioner at Pacific Skin Institute, and Kristin Neumann, founder of MyMicrobiome. Below, we bring attention to key points from their discussion, including when a product should be patch tested, why in vitro testing is the best route for the skin microbiome, and how much clinical studies cost.

HUMAN PATCH AND IN VITRO TESTING

Even if a product is formulated with ingredients widely known to be safe, Weiss stresses testing remains imperative. There are different rounds of testing a brand can go through. For pre-clinical testing, brands can opt for a toxic risk assessment typically done by a toxicologist or someone “educated enough to understand what they’re looking at,” says Weiss. He recommends this route for formulations with newer ingredients that may not have a well-established toxicity profile already. Next is testing for dermal and ocular irritancy—Weiss suggests this testing be done for any face products—and quality assurance. These sorts of tests are done via in vitro or not using living organisms.

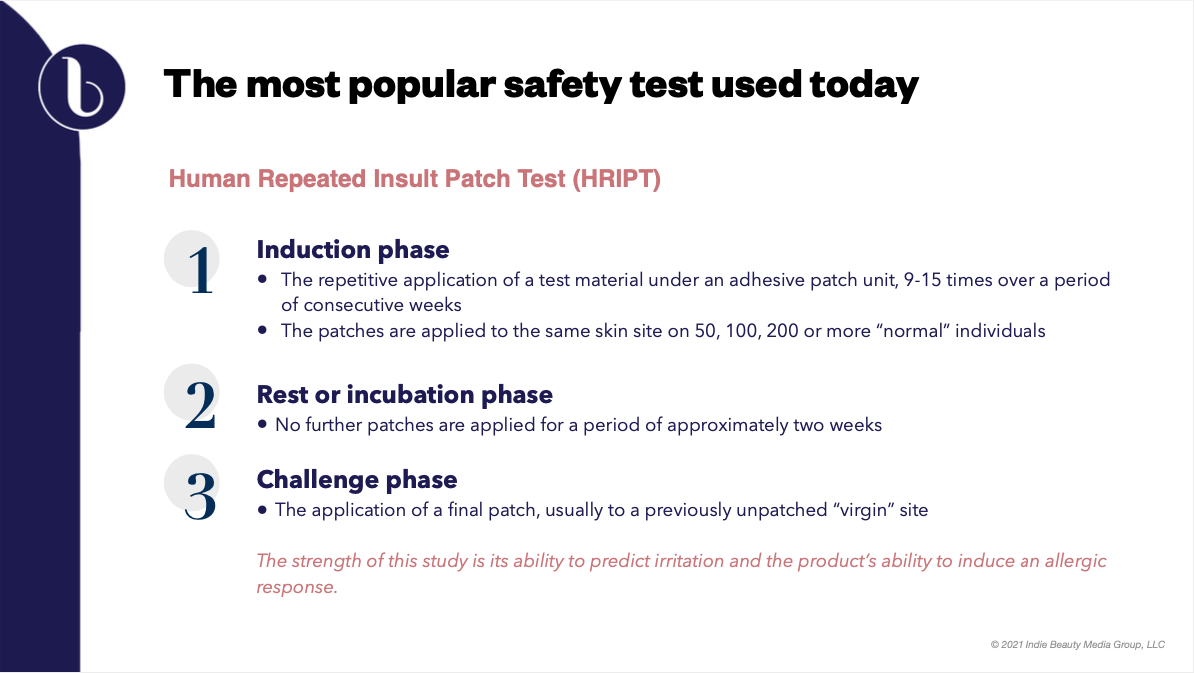

Weiss points out the No. 1 test worldwide for cosmetic safety right now—and the one he recommends the most—is the Human Repeated Insult Patch Test (HRIP). It involves repeated application of a material over the course of a couple of weeks on 50 to 200 test subjects. After a brief rest period, a final patch is applied to a virgin patch of skin. Weiss says, “The strength of this study is its ability to predict irritation and the product’s ability to induce an allergic response.”

Testing on humans is cheaper than extensive in vitro testing. Weiss says, “To get to your endpoint with in vitro, you have to run multiple tests, where the human repeat insult patch test is relatively inexpensive, and it gives you the two of the major answers you need…If you have the right operators who know how to judge these things, you can get a lot of information from one test.” Though there are instances when a brand can’t conduct a patch test like if a product contains known irritants, Weiss still believes it’s a good test from a value point of view.

Pro Tip: If a brand bypasses safety tests altogether, its product is considered misbranded, says Weiss. The United States Food and Drug Administration requires products that aren’t tested for safety to have a label that reads, “Warning: the safety of this product has not been determined.” Weiss advises against this route and, in his 30-year career, he’s never seen the label on a product. “By using that warning label, you are opening yourself up for a huge amount of class action lawsuits, especially in the state of California where it’s very easy to certify a class-action lawsuit even with safety testing,” he says. “It’s very much worth doing safety testing to protect yourself.”

Product Testing Fit For The Microbiome

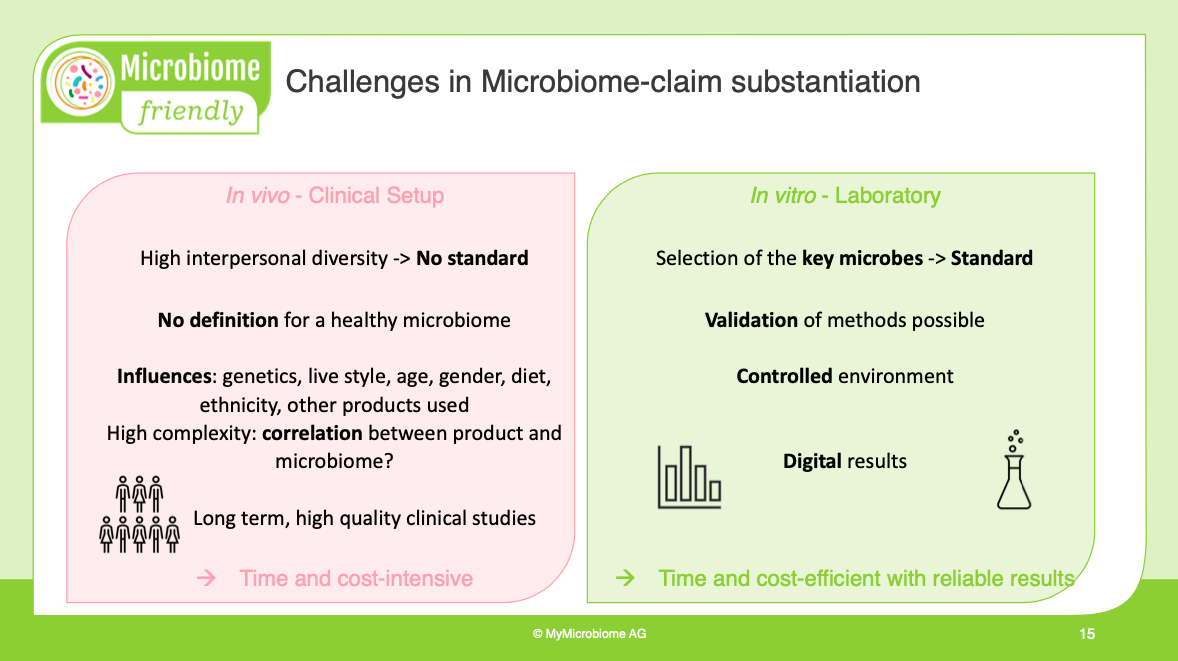

When it comes to the microbiome, Neumann underscores in vitro testing is better. “There are clinical setups for every claim you are making in the cosmetics industry, but, for the microbiome, it is way more complex because every microbiome is very different from each other,” she says. “There’s no standard available, so you cannot have one test on humans where you will always get the same results with the same product.” Plus, she details there are influences like genetics, lifestyle, age and diet to factor in. “This is all adding up to the complexity and makes it very, very difficult to have a really good clinical study that shows the effect of a product on the microbiome,” she says.

With in vitro testing, it’s a controlled environment. “We have the same microbes and the same numbers, we can validate those methods and get the digital results,” says Neumann. “So does that product kill the microbes or doesn’t it? Or does it nourish microbes or not? In vitro and laboratory results are time and cost-efficient, and get reliable results compared to clinical studies.” A high-quality clinical study can cost millions of dollars and take months to conduct, while Neumann shares that, in her in vitro lab, a test typically takes around two weeks.

Pro Tip: The skin microbiome is very complex and the science around it is young, mentions Neumann. “We don’t actually know how to improve the microbiome,” she says. “We only know that the best thing you can do is actually to leave it alone.” When formulating a product, though, there are ingredients that Neumann says can be an issue for the microbiome, depending on the amount and the final formula. The ingredients include essential oils, fragrances, and certain preservatives and alcohols.

Neumann isn’t a fan of bar soap because she says it can remove beneficial sebum, bacteria and skin lipids. On top of relying on microbiome-friendly products, among the other ways to proactively protect the skin microbiome is exercising, interacting with nature, eating unprocessed foods, avoiding over-cleansing the skin and even getting a dog. “It has been shown that dogs, not cats, are really good at enriching your microbiome diversity,” says Neumann.

Study Design And Costs

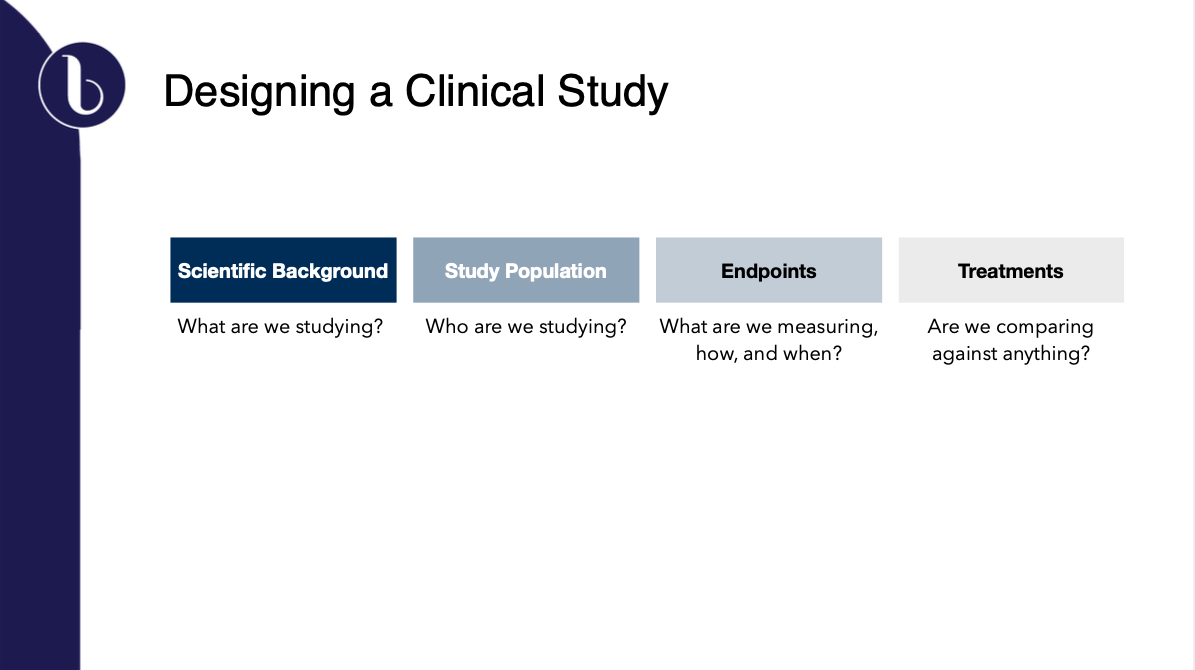

Clinical studies are means to substantiate performance claims and offer brands legal protection. When setting a clinical study up, it’s vital to consider what’s being studied, who’s being studied, and what’s being measured. Sivamani says most brands are looking to measure endpoints like redness, wrinkles and uneven pigmentation. He notes that who a brand is studying is almost as important as what it’s studying.

“If you’re studying, say, early wrinkle formation in someone, and you want to see if that gets better, you probably want to study a population that tends to form wrinkles at a faster rate,” he says. “You want to go after the population that might give you the best chance of getting some sort of a difference.”

Pro Tip: “One of the big questions that comes up is, well, how much does this all costs? Is this going to break the bank for us?” says Sivamani. The cost depends on a few elements. The number of people in the study is one of them. “This is very important because sometimes people will come in and say, ‘I only want to recruit like eight people or five people,’ and, if you don’t have statistics, you’ve just wasted your money,” says Sivamani. “You want to have enough people so that you can make a reasonable study out of the whole thing.” For a pilot study, 15 to 20 people is a decent number.

What’s being measured and for how long, and regulation can also drive the price up, says Sivamani. On average, he figures it can cost $400 to $500 per visit per subject, which, in total, can come out to be in the tens of thousands of dollars. Sivamani says, “On the flip side, if you do a study that’s going for FDA regulation, all kinds of reporting, making sure that you have every single regulatory factor taken into account, and you’re also going to be putting the data together with third-party sort of statistical analysis, I mean, now you’re talking millions of dollars.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.