Iris Finance’s Drew Fallon On Why The Gap Between Brand Haves And Have-Nots Is Growing

Drew Fallon, CEO and co-founder of Iris Finance, an AI-powered finance data platform for consumer packaged goods brands, believes the worst of the direct-to-consumer reckoning is over. That doesn’t mean he believes the path to success is getting easier for small consumer brands.

“The P&Ls of these businesses are just getting absolutely crushed,” says Fallon, former CFO of Mad Rabbit. “You have to be that much better at demand planning, cash-flow management and distribution.”

Iris Finance is banking on brands turning to it as they button up their finances. Since launching in April, its client roster has reached 65 brands with $2 billion in gross merchandise value. The brands generate between $1 million and $500 million in annual revenues, and they’re roughly evenly split between those generating over $15 million and those generating under that amount.

By the end of this year, Iris Finance expects its client roster to hit around 200 brands. A year from now, Fallon’s goal is for that client roster to expand to 1,000 brands achieving $8 billion to $10 billion in GMV.

In the tough environment for CPG brands, he says, “The reason Iris has experienced the level of traction that we have so far is there’s just a natural tailwind to it. I don’t know that if you tried to sell Iris into this market four or five years ago that it would do very well because people didn’t really care as much as they care now.”

Beauty Independent spoke with Fallon and Alexander Heckmann, his co-founder at Iris Finance, about why they’re big on TikTok Shop, the rise and rise of customer acquisition costs, distribution diversification, the right way to use fintech lenders, CFO roles in the CPG universe, and the growing chasm between big and small brands.

How did Iris come to be?

Fallon: I started my career in investment banking and fell into the founding CFO role of Mad Rabbit. Most out-of-college investment bankers don’t end up going to work for very small startups. I spent about five years running finance, accounting, supply chain, logistics, basically all the boring stuff, for Mad Rabbit. Over time I started to realize that there was a pretty glaring lack of financial infrastructure and rigor within the community. Traditionally, this industry has been very marketing focused.

I was getting consulting requests from folks wanting help with financial analysis or forecasting. It would be impossible for me to service as many people that were asking me for help. So, I thought to myself, I can’t really do this myself, but I bet this new ChatGPT thing could do it. I called up my friend Alex. He was the brightest software entrepreneur that I knew. He had recently exited his last business.

We decided to bring Iris to market over the last 12 months. It’s under the value prop that brands don’t typically have a robust understanding of their financials and don’t do a very good job of forecasting. We are the AI-driven software that’s going to help democratize financial intelligence and literacy across the ecosystem.

What does Iris do, and how much does it cost?

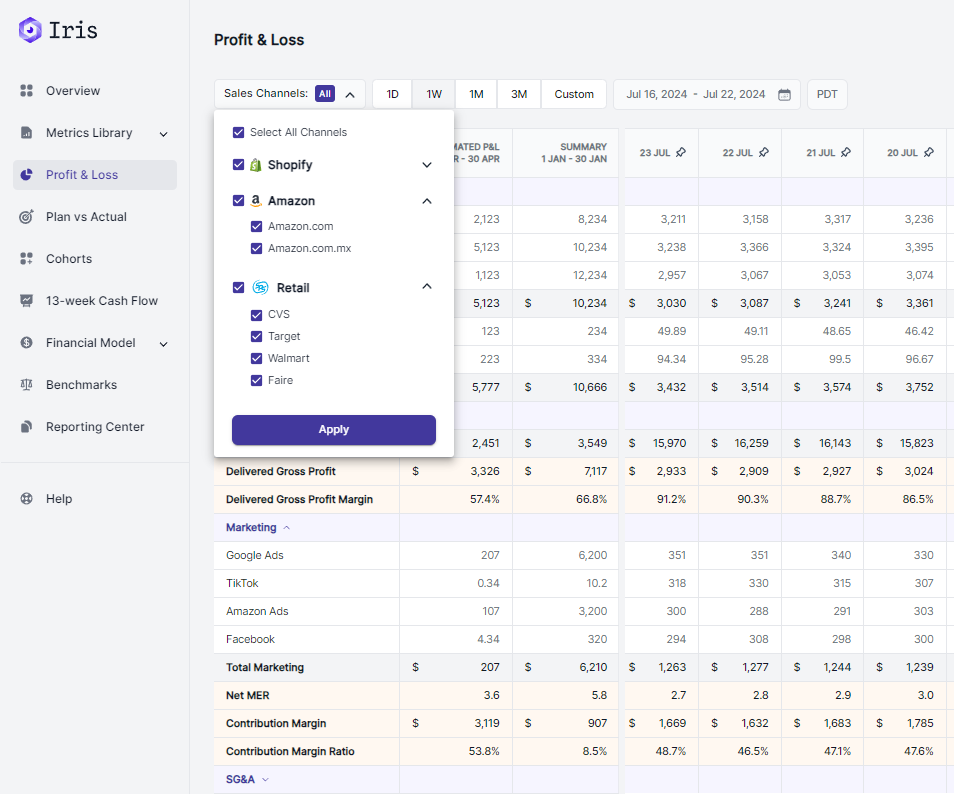

Fallon: What we do is we connect into all their APIs that would produce a revenue or an expense. That’s typically things like Shopify, Amazon, EDI for retail like SPS Commerce or TrueCommerce.

We connect to your Facebook, Google, TikTok, accounting ledger, payroll system, bank accounts, basically anything that we can get our hands on create a set of real-time financial statements, which provides operational visibility to be able to answer, how much money did I make yesterday or the day before that and the day before that?

It also gives us the ability to understand all of that data and roll it forward into our forecasting models. Not only are we giving operators enhanced visibility into the financial performance of their business in real time, but we’re also taking those trends and forecasting it out with cash-flow models and strategic financial models. You get this backwards looking analysis feature and this forward-looking forecasting feature all wrapped into Iris for about $1,000 a month.

Beauty businesses that have struggled often identify not hiring a CFO earlier as compounding their struggles. What are your thoughts on that as somebody who’s been a CFO at a CPG brand?

Fallon: It’s important to define the term CFO. Historically, the CFO has been a very backwards looking, knows GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) inside and out, can institute proper controls, very much the CPA. The classic idea of the CFO is not good for an earlier stage business. You would need to be doing $50 million or $100 million before you need a proper CPA running your back office.

If we talk about the modern CFO as somebody who can be more forward thinking, can understand the implications of advertising dollars on unit economics of a business, there is never a too early time to put somebody in like that.

Founders are generally marketing-oriented people, and there’s a mystery around finance as a school of thought to them. What they struggle to sometimes realize in my opinion is that the advertising component in DTC and CPG specifically is such a significant part of the financial complexion of any business that, if you can understand the advertising component, you understand 75% of what there is to understand about the financial movements of the business.

To the extent you can find somebody who’s grounded in finance, but understands how a change in CPM can influence CAC, those people are among some of the most valuable on the market right now.

Despite small DTC brands closing, the Shopify universe is growing. Assess what’s going on in DTC today.

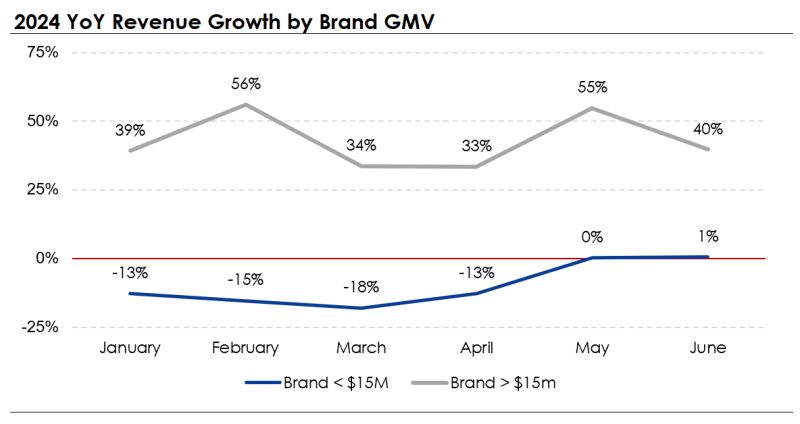

Fallon: Iris has several brands doing over $100 million in annual GMV. If one of those brands is growing 20%, so they’re adding $20 million this year, that is enough to account for 20 $1 million-a-year business going under. People think DTC is shrinking because the number of brands in DTC is almost certainly shrinking. However, the cumulative GMV going through existing brands is going up because you’re seeing the rich get richer.

It’s much harder to be a small brand. I’ve been in that seat. It was significantly harder doing a couple million versus $20 million. When you’re doing $15 million-plus, you’re selling in multiple channels, you have a real product line, your advertising is diversified. So, we’re seeing a lot of these smaller brands get wiped out.

You could almost see every single small brand under $1 million die out, and it would take so many of the bigger brands not to be growing at the same pace that they are for that to cancel out. That’s why you see Shopify, for instance, attacking the enterprise cohort of customers where all the growth is.

Whey do you see the gap growing wider between brands under and above $15 million?

Fallon: iOS 14.5 was a significant tipping point. It took two years for Meta to really figure that out, and they continued running into problems. As far as the Shopify ecosystem is concerned, there’s not a doubt in the world that it’s harder to get to $15 million today than it was two to five years ago from a unit economics perspective. Think about inflation. If I’m selling a beauty product and I’m sourcing packaging for 75 cents four years ago, that could very well be $1.20.

Prices have gone up, not only from the cost of goods perspective, but also from the advertising perspective. You also have retailers that are really cracking down like Target, Walmart. Last year, Target started wiping brands out. Now, you’ve got entire retail channels that are not taking new brands in. For the foreseeable future, the larger brands will be advantaged in terms of surviving and continuing to grow.

How diversified is your clients’ distribution?

Fallon: Successful brands have been very DTC-focused for a while have recently begun to embrace either a secondary or tertiary channel. There’s plenty of brands that have gotten to $20 million, $40 million, $60 million in DTC revenue, but then over the last year or two a lot of their incremental growth has come [elsewhere] because they’re now considering Amazon a more primary channel or they’ve finally decided to go into Target.

The biggest brands that we have are still mostly DTC, but it’s not the most quickly growing part of their business. Their Amazon business is growing significantly faster on a year-over-year percentage basis than their Shopify is or their retail is going from seven to eight figures this year.

There hasn’t been enough time for their channel mix to have gotten equal or even a third as far as retail or Amazon goes, but you’re seeing more willingness to expand into those channels than you would’ve five years ago when they were like, why would I go into Amazon? They take 35% of every dollar that I make. Their biggest channel is still DTC, but it’s not the primary source of their ongoing growth.

What’s their CAC looking like today, and how do you foresee it going forward given the environment?

Fallon: In short, CAC has been going up. It’s worth noting that Iris actually computes in Amazon CAC as well, which is fairly differentiated, but really we’re talking about Facebook, so this is going to be 70%, 80% Facebook spend. Given the nature of the auction system within Facebook, that auction is not getting less popular. The arbitrage effectively has been squeezed away. I don’t see CACs ever going down ever again.

They’ve never gone down in the past. As long as Facebook has been around, they’ve only gone up, and they will only continue to go up. The biggest brands are getting bigger because they’re the ones that can afford the CACs. There’s not even a market for low CACs anymore big brands dominate the bidding markets for ad placements. Their tolerance for a higher CAC is so much higher than small brands.

It’ll level out over time. It’s not going to go up every single year forever because the market will reach some sort of equilibrium. However, I don’t know that there is a strong case for any significant year-over-year decrease in CAC anytime soon unless TikTok grew a 100X in the next year, but TikTok is such a small part right now.

TikTok has been subsidizing brands participating in it. Is TikTok Shop meaningful for your clients?

Fallon: We are in beta with a TikTok Shop integration right now. I would not have allocated our resources to building that out if I didn’t think that it was going to be worth it. We have a lot of brands that do extremely well on TikTok. There’s eight figures of revenue in Iris on TikTok Shop, probably close to nine. I think every brand should be doing it because TikTok Shop today is what Facebook was in 2015. It’ll be interesting to see whether it has the same staying power as something like Facebook.

There is a huge arbitrage opportunity within that channel. Subsidizing is just another way of saying arbitrage. You can go on TikTok and take advantage of below market customer acquisition costs effectively. TikTok Shop has at least a couple of years in it. If they get the adoption that they think they can, then maybe it does turn into the next Facebook or Shopify. I would be willing to bet on it.

Will TikTok Shop yield the next Glossier?

Heckmann: Why not if the right creator launched it?

The reason TikTok might not be able to yield the next Glossier is because it seems to be driven by discounting and goods competing with Temu more than brand building, although that’s definitely not the entirety of the ecosystem.

Heckmann: In the earliest days of on Instagram, it was actually eerily similar. Once upon a time 10 years ago, you had low quality influencers pushing products like tea for belly fat. Then, you evolve.

There’s two ways to look at it. It could stay low quality if TikTok isn’t going to invest. The other side of it is TikTok is so nascent in its development when you consider Facebook or Instagram’s arc that the platform will start to mature and give people the ability to have staying power and better shopping experiences if they think that their enterprise value could go from call it anywhere between $250 billion and $500 billion towards a trillion-dollar asset.

So, it’s about, do you think TikTok will try and take a real swing at Facebook’s audience and build staying power?

If you had millions to sink into a brand today besides Iris, would you try to create the Glossier of TikTok?

Heckmann: I don’t necessarily think Glossier is the best example. I think it’s one example. Would I build a brand on TikTok? I would. It wouldn’t be the same linear strategy of just buy ads. There’s a lot of successful brands on TikTok right now that a lot of people haven’t heard of.

Fallon: Without a doubt, every brand owner should be at least experimenting with the platform. I’ve seen 50% contribution margins at seven, eight figures in that channel, and it’s free money almost if you can get it right.

What skill set should a founder starting a brand today have?

Fallon: In 2020 to 2022, even if you had a fine idea for a beauty product, you had a bit of a resume and you made a pretty package, you could probably raise $500,000 to $2 million to get it off the ground. There was so much money in the system in the pre-seed seed stages that that money had to find a home, and it found a home in founders that probably would not have gotten that money if there was less of it in the system.

Now, more than ever, you have to know your numbers. You have to be able to describe your unit economics, not only certainly to any prospective investor, but also to yourself because the odds that you’re going to get any capital are near zero. If you don’t know your unit economics and cash flow, you won’t have a business.

The founder that knows their numbers and how to scale the business in a healthy and efficient way is the founder that will prevail. We’re 18, 24 months into this reckoning, if you will, and there’s not many still around that don’t know those things.

What are moves you’re seeing clients make unlocking more profit that may not be obvious to outsiders?

Fallon: Shrewd operators are almost obsessively searching for optimization. They’re not scared to fail with experiments. They say, “Hey, I’m going to put $25,000 into testing TikTok Shop over the next two months, and if it doesn’t work, then fine.” If it does, that’ll pay itself back almost instantly. That’s from the revenue perspective.

From the expense perspective, there’s a lot of savvy operators that have found fantastic ways to leverage emerging technologies to save money. There are popular AI-enabled customer service agents that save money on a per ticket basis. There’s AI tools that can save you money on hiring a data team. The payroll as a percentage of sales over the last three years I bet has been going down dramatically. You don’t need to hire that incremental person as soon as you used to.

For a new brand today, how’s its team going to be different than it would’ve been in recent history?

Fallon: If I was to start a brand today, I would do as much as I could to lean into organic from a marketing perspective. I would partner with somebody who had an owned audience, and I would also probably be less quick to dive into a talented media buyer as that arbitrage goes away. Within Facebook specifically, the premium that used to be placed on great media buyers has gone down. Media buying is mostly commoditized these days.

People have gone away from paid media investing in personnel and more into investing in personnel on the organic media side. Some people are doing more owned and operated retail stores because it’s a giant billboard for their brand. And the focus has definitely shifted away from optimizing the arbitrage within the Facebook ecosystem and into a more healthy long term as far as generating content and awareness around a brand, not just spamming people’s Facebook feed until they buy something.

What are you watching for the rest of this year?

Fallon: Black Friday will grow year-over-year. As far as the general ecosystem, I think all the stuff that we’re talking about is behind us. I mean, we’ll see a lot get announced in the next six months, but things that get announced in November or December, they happened in June. Even the Ampla stuff, people didn’t really get ahold of that until six months after it happened, and I think, for the most part, the damage has been done.

I’m excited to continue to watch brands diversify their point of sale distribution and getting into retail or finally launching on Amazon. A lot of people are starting to do Faire even. We’re building a Faire integration because I’ve talked to more brands in the last months that are selling on Faire than I ever even thought existed.

You mentioned Ampla. How should brands smartly use those sorts of financial tools?

Fallon: You use them smartly by not being dependent on them. They are a tool, not your lifeblood, right? They’re commonly used for inventory financing. If you structure the terms in a way where you can use it appropriately, then there’s nothing to worry about. The problem is really that nobody knows how to use them properly.

I personally would not predict the fall of another fintech lender like Ampla. We anticipate rate cuts this year that we were supposed to get before. Lenders will be just fine, and they’ll have made it past the worst.

When you say that people aren’t using the lenders smartly, can you explain?

Let’s say you’re a business that does $5 million a year and you raised $1 million to start that business so you have $1 million in equity on your balance sheet. Your business is growing nicely, and you decide that you want to accelerate the growth by taking out a merchant cash advance loan from Wayflyer, for example. They give you another million dollars. Now I have $2 million of cash: $1 million of equity, and $1 million of liability.

I have $2 million to get from $5 million to $10 million. I step on the gas of ads, and my unit economics fall into the red. Now, I’m paying $40 of CAC on a $50 order when I was paying 20 before, but I’m growing, so it’s all good. What you’re doing is, when you start to generate negative contribution margin on a per order basis, you’re just burning through that $1 million of equity that was on your balance sheet because the lender’s got to get paid back somehow.

These brands get loan money from these players, and they basically use it to wipe out their equity because they just want to grow. They don’t necessarily take a hard look at their profit margins or their unit economics. That just means they have to take out another loan from one of the lenders to leverage future revenue further.

Really what you should be doing is saying, I’ve got a working capital cycle that’s getting pretty skinny right now. I think I can grow a ton in Q4. I’m going to borrow from one of these lenders, and I’m going to build up my balance sheet with inventory. Then, I’m going to liquidate it all out by the end of Q4, and I’ll pay them off. I’ll do the same thing next July.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.