XRC Labs Venture Partner Andrew Ross On Channel Economics, The Relationship Between Strategics And Small Brands, And A Pomade He Loves

After almost six years at The Estée Lauder Cos., where he was EVP of strategy, new business development and integration, Andrew Ross joined XRC Labs, a venture capital firm and accelerator founded by Pano Anthos in 2015 and sponsored by Lauder and The TJX Cos. Inc., among others, last year as a senior advisor and venture partner.

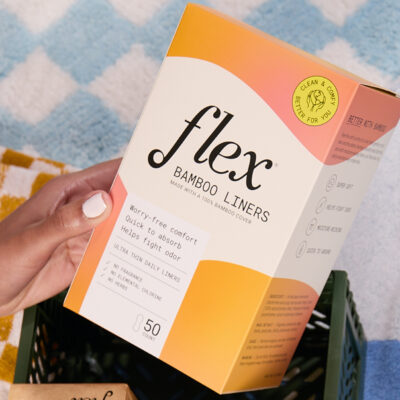

The timing wasn’t a coincidence. Along with bringing Ross on board, XRC Labs launched its Brand Capital Fund in 2022, which participates in seed and series A rounds in the beauty, personal care, home, and health and wellness categories. SolaWave, the skincare device brand hitting 650 Ulta Beauty doors on March 5, is its first investment.

“XRC is an accelerator, but also a targeted venture player now, and I’m helping as XRC expands into that space with looking at potential brands to invest in from the venture side and as an advisor for the brands that are in the accelerator, too,” says Ross. “XRC is very close to founders, but very close to strategic players as well. So, being close to the market, but also knowing how strategic players are, what they’re looking for and what is a good investment allows XRC to play beyond the traditional accelerator role.”

Beauty Independent picked Ross’s brain for insights on the state of the beauty industry, including when large strategic players should get involved with smaller brands, why fragrance is an attractive category, the oft-ignored importance of channel economics, and what indie beauty brands should know about securing funding in the current environment.

Over the last several years, venture capital has ventured more into beauty, but a lot of people don’t believe venture capital works well in the consumer goods arena. What is your take on that?

It is all about expectations of valuation. I believe the mismatch in that space has often been where a venture fund is more used to looking for tech multiples. A poster child would be Glossier, for example.

If you have a better sense of what the longer term valuation should be for a beauty company, it’s still a very attractive space compared with a lot of other ones, but it’s not going to be at sold at a 20X revenue multiple. So, I think it’s just making sure that there’s a greater alignment of valuation in the marketplace on what you should be expecting in terms of what things will be sold at.

How are strategics changing their thinking about where they can play with smaller brands?

Some things change, and some things stay the same. As a strategic, I would be looking for a new engine of growth within the portfolio of the company. To be material whether you are Estée Lauder, L’Oréal, Shiseido or you name it, that has to be a brand that you believe has the potential to ultimately get to something that is several hundred million dollars and profitable or even a billion dollars and profitable. We are trying to bring that perspective to the brands we are looking for at the Brand Capital Fund.

Lauder acquired Rodin, and it didn’t seem to work out that well. Do you feel we are going to see examples of that in the future or are strategic buyers going to move away from those very small brands?

I think that there’s two forces at play. Every strategic has tried and failed to make direct investments in brands like Rodin, for example, and realized that there are things that are too small and end up, however good your intentions, getting hugged to death.

At the same time, strategic players are not excited about a traditional path that goes from founder to venture to PE to strategics, where you are essentially at the end of the food chain being expected to pay a large multiple for something where somebody else has created the vast majority of the value already.

So, it’s about finding the Goldilocks relationship or structure where, as a strategic, you are participating and learning about brands at early enough stages where you can pull the trigger when it’s early enough to be right for you to add value.

I think the sweet spot is $30, $40 million topline, where you know what you can still do in terms of extra distribution, and you know the value you bring from other capabilities you have like supply chain procurement, but you are not going to be, for example, trying to integrate a Rodin brand into an SAP system, which is not a very good idea.

Lauder has taken relatively small stakes in companies like Deciem and built up from there. What do you make of that model?

I’m one of the architects of that model, so I think it’s a really good one, and I think that is the model of the future to be honest. How do you get close enough to a business where you still capture the entrepreneurial drive that you get through VC and PE funding, but you get the ability to help guide a brand as to what is the best way to fit within a strategic portfolio?

They say, on average, 50% of acquisitions work. If you can turn that dial and be doing something that can get to 65% of acquisitions working, it’s just a huge amplifier of value creation. I think you’ll see that happening more and more.

What shifts are you watching in beauty and personal care that you think will have substantial impacts on the market for years to come?

The first one that’s playing out involves the move from a traditional branded company to a celebrity/influencer being the way to drive a brand. Content creation and community has changed fundamentally, so the marketing playbook has completely changed, but I think it went too far [toward celebrities and influencers], and now people are realizing that you actually need other capabilities to be able to create a brand that’s sustainable long term.

It’s about finding the right sweet spot between what’s an authentic role for celebrities and influencers, and combining that with more traditional, disciplined brand-building skills to have a brand that lasts and makes money.

The second one is channel convergence. There used to be a real hard line between prestige and mass. Those lines are blurring all over the place, whether in Europe or North America at Ulta, Target, Sephora or Kohl’s, and I think that’s still something that hasn’t completely played out yet.

There’s a lot of dynamics going on. What does prestige mean? What are the lines between mass, masstige and prestige, and what does that mean for brand building versus brand leveraging versus brand destroying?

The other one is sustainability. We had clean, now clean doesn’t mean anything to the consumers. How does that evolve? Are consumers going to value that enough to actually pay for what it takes to develop a sustainable value chain or is it still something that doesn’t really make that much difference? If you don’t get payoff on your lipstick, are you going to say, “I don’t really care about sustainability?”

In a market where prestige and mass are converging, what about luxury?

Luxury is a tier within prestige. The question is, does it detach? Does it evolve in a different way by region? Another big question is, what is going to happen to the Chinese consumer?

I think you are seeing luxury increasingly being defined East to West rather than West to East. So, the heart of a luxury brand’s equity is moving towards Shanghai and Hainan. Even though it may be drawing from the West, the execution of luxury is becoming more and more targeted towards that Chinese consumer. Is that going to stay, or is that going to change?

And another great question is, what is the luxury distribution channel of the future? I don’t know the answer. Barneys is closed. Bergdorfs is still there. Saks is going to have a casino built on top of it. Does luxury still start in Sephora or does luxury start someplace else for as far as beauty’s concerned?

I think you are starting to see luxury moving in some respects into the professional channel. It’s focused on experience. Is it going to be more about buying as an experience as opposed to buying in a shop?

Let’s go from luxury to mass. You’re on the advisory board at Bubble, which has been a darling in the mass market. What’s your view of what’s happening in the mass market?

I have to pause and just acknowledge [Bubble CEO and founder] Shai Eisenman is an amazing person. I’m an advisory board member, but I probably learned more from her than she has learned from me in terms of our relationship so far. She’s an unbelievably good founder who I think actually has challenged old-fashioned strategic beliefs that I may have had. That’s what you’re looking for from startups and founders.

The old playbook would say you can’t build a brand, especially in beauty, in Walmart. She has proven that wrong, at least so far, and I don’t see any sense that that’s not going to be the case. That’s obviously something Walmart’s really interested in proving wrong as well.

The time of mass is obviously right now. People are thinking very hard about value. I still believe in Mr. Lauder’s lipstick index. That is actually showing to be true not just in makeup, but that’s also shown to be true in haircare, too. People are willing to spend money on things that make them feel better and look better, which is a great thing for the category.

Mass, whether it be Walmart or Target, understands that there is a space to build and showcase new brands as opposed to just embracing the old packaged goods model. Indie brands have consistently taken share in prestige for quite a while now, and there’s the model where the larger companies find the winners and acquire them to gain share as well as driving great brands that they’ve owned a long time. I think that dynamic is going to start to play out in mass, too.

You have in large incumbent brands that are going to start to be a target for indies, and retailers are looking for newness and something interesting, whether it’s to build baskets or get new customers in. Bubble is a great example of that. The product is amazing, it works great on everybody’s skin, but it definitely is a gen Z-focused brand that can get new customers into Walmart as well as get them to trade up.

It’s good for category the category economics, it’s good for the customer count, it’s good for the longevity of Walmart to know that they can get new customers in. I think that beauty as a category is going to be something that mass retailers are going to pay a lot more attention to.

They’ve also learned how to work with smaller startup brands, which is you basically can’t expect them to invest all the money in working capital and then not pay them for 90 days because you’ll put them out of business. So, I think there’s a lot more of a founder-friendly perspective from retail in that mass space.

Are you convinced by the men’s category?

I’m convinced that there is a huge opportunity for men to increase their usage in beauty categories. Am I convinced that anyone has unlocked that yet beyond shave and beard? No, but the person that does is going to make a lot of money.

Stryx is a good example, which is part of XRC’s portfolio. They’re trying to unlock something really interesting, which is how do you think about makeup in a way that actually makes sense for men? You can see that already happening in Korea and China, but Korea especially, and how to port that back into a North American sensibility I think is a really good [place] for somebody to be in.

You are also a board member and advisor for Barb, an LGBTQIA+-owned brand for short hair. Why do you think that brand has legs?

Pano introduced me to them before I ended up working in partnership with the folks at XRC. It has great founders, an amazing purpose-driven story that makes you want to champion the brand for what they’re doing, and a product that is really good, which is sometimes the thing that’s missing from a lot of startups that bought a white-label product, and it’s all about marketing.

The pomade works really well, and it smells great. It appeals to a much broader range of folks than is the center of the target. It has a lifestyle opportunity beyond beauty. So, it checks a lot of boxes, and good human beings are involved in the brand to begin with that are trying to do better things in beauty in terms of representation and the way people feel about themselves. What’s not to love about that?

How do you see distribution models and where people want to shop shifting?

During COVID, you basically saw online jump five years over projected growth. Then, I think the thesis was it was going stick there, and now it seems to be coming back a year. People are desperate to get outside and actually interact, but ultimately the convenience of online is hard to beat.

It’s still not great for brand discovery, and that’s where you’re seeing people realize, both for economics reasons and for consumer reasons, that you need to have a blend. What’s a discovery journey, and what’s a replenishment journey?

People used to think discovery was DTC and going to your website—and maybe it’s not. Maybe actually your website is much more about repeat, and how do I make it as easy as possible to make sure that my repeat rate is as high as possible and that I’m actually building a longer term relationship with the consumer? But I still need to be out there in the marketplace being discoverable. How to think about the economics by channel is the next real question for people as they grow their brands.

Everybody spends a lot of time thinking about category economics—What’s my best gross margin? What’s my worst gross margin? What’s my highest repeat rate? What’s the lifetime value of my customer?—and I don’t think people pay enough attention to, what’s my channel strategy, and what’s the economics? What’s the P&L by channel look like, and what can I do to make sure that I optimize that?

What margins am I willing to give retailers, and what am I not? How long are they going to be invested in a brand or am I just cannon fodder of newness for them? All of those questions I think are super relevant and probably underthought through versus the category lens, which is normally what you would start with, which is, “What’s my margin on my moisturizer versus my cleanser, and how am I pricing them?” It’s just as important to think about what my economics are by channel as it is by what the products I’m selling.

As an indie brand, how do you guard against being in and out of a retailer?

If I knew the answer to that, I should start my own brand, but I think it’s being conscious of it. So many times when a retailer reaches out to you and says, “We’re interested in having you,” that’s almost like getting your first term sheet. It’s a moment of celebration, and I think you need to work on, what’s the terms both in terms of what are they going to use me for, and how much commitment do they have to the brand strategically? Am I part of a 25% newness goal that they’ve established, and they don’t really care that much about me?

Retail is real estate. You have to earn your keep right from day one. Think about velocities. You need to know that you are going to sell at a rate that is competitive. They will not have that much patience to let you work that out on the fly.

Sage advice for founders is to make sure that they are really confident that it’s the right time to go into retail, that you have enough of a following, enough confidence in your product-market fit and your repeat rate that you’re going to be doing a competitive level of velocity on the shelf.

What do you think brands might be overlooking when they get that first term sheet?

Less so now, but I think before they were always too focused on the valuation versus what can I do with this money and is there incremental value that comes along with this money or is it just basically I’m going to have somebody that doesn’t know anything about my industry sitting on my board?

You can get value from lots of things. You can get value from an understanding of the capital markets perspective. You can get beauty expertise or food or beverage expertise. But too many people were too focused on the headline valuation because they felt like that was basically the first step in a guaranteed upstairs valuation staircase. In the last year and especially the last nine months, everybody has been disabused of that.

Last year, there was the big Byredo acquisition. Where do you see the fragrance segment heading?

The underpinning attractiveness of it I think is that we’ve learned that fragrance is almost the most personal. You might think it’s skincare, but skincare comes down to a number of ingredients, and you have the right recipe for yourself. I think fragrance is more like fashion, you can find your signature style. You get to the point where you feel, “This is me.”

Before it was almost like a movie model, which is I’m excited about the celebrity or the famous person that they are using to advertise Coco Mademoiselle or Rive Gauche, whereas the artisanal space is something that feels more like you as opposed to borrowing somebody else’s equity. It is a really personal choice. That means you’re super loyal and loyalty drives repeat rate, drives profitability. Plus, you’re not having to pay 6% to somebody from whom you’re licensing the brand.

It’s a really attractive space. Economically, it’s great. Consumers love it. It gives them a lot of pleasure to feel like they’ve really found what expresses them. You can get that from a personalization standpoint. One of XRC’s portfolio companies is Scent Lab. That’s coming at that more with candles, but it’s the same sense of you can find your own scent that expresses your personal equity.

If you were at an indie beauty brand, how might you think about getting funding in today’s market?

This market is 180 degrees from what it was a year and a half ago. Have a ton of patience and resilience because people will be asking you all kinds of questions that they weren’t asking before. If you can raise, raise enough to carry you through for longer and have a more realistic expectation of the value of what you’re going to be raising. That’s still a gap that needs to close in some respects, especially in the beauty space.

It’s economics, economics, economics. That doesn’t mean to say people are ignoring the consumer, but the consumer has to be linked to the economics. Show me that you’ve got the right architecture in your P&L from the start. It may not be delivering on that right now, but show me that you’ve thought about the gross margin profile that’s going to be able to fund something that’s going to get me to a free cash-flow positive business as quickly as possible because that’s a positive flywheel.

You don’t have to be profitable from day one, but you have to be able to show that you’ve thought through what it’s going to take to be more self-funded rather than go through series A, series B, series C and then it’s the strategic’s problem to fix the profitability. No strategic is going to be interested in having a conversation with you. And the IPO market is probably going to be still closed for a long time. I don’t know why people were investing in IPOs where there was no profitability.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.